At 2am on Jan. 25 this year, I was sitting in my pajamas on the couch of a rundown hotel lobby in Asyout. Around me were eight policemen in civilian clothing, leaning their semi-automatic weapons against their knees, in front of me two officers who had taken me from my room half an hour ago.

They had my ID and were going through my phone to see if I had posted any political statements on social media. Those were tense days; the Muslim Brotherhood was entrenched in a deep battle with the regime, just one day before the police headquarters in Cairo had been bombed, and the day before that five policemen had been shot in cold blood in a night raid on their checkpoint.

None of my answers satisfied them. Why was I in Asyout? Why was I driving instead of taking a plane? Why was I taking pictures in public? I was nervous: They were not completely aware of my American companion in the room upstairs.

In a time when everyone was a potential spy, when Yara Sallam gets three years for unfounded charges and Peter Greste gets 5-10 years solely for being a journalist, whatever reason brought me to Asyout was not comforting enough to them.

As if that wasn’t enough, the TV behind me started showing the music video for “Teslam el Ayadi”, the popular pro-army anthem. The officer pointed at the TV.

“What do you think of this song?”

To explain how I ended up in this situation, I have to talk about a virtually unknown place in Egypt: the Abu Zaabal Leper Colony.

The leper colony is located an hour north of Cairo, well hidden in the no man’s land of Abu Zaabal, surrounded by vast desert and military factories. Since its founding in the 1930s, it has gone from dire circumstances and lack of funding to a relatively well-organized government facility.

Thanks to funding from various NGOs and volunteer work from individuals, organizations and churches, the almost 1600 lepers and their families can be treated and provided with shelter.

A cure for leprosy, a bacterial disease causing severe disfigurement of the extremities that has defied the millennia from ancient China to today, has hit the market only a few decades ago, which is why most of the older generation of lepers still bear the scars, and younger patients are able to get treated before the disfigurement sets in.

Contracted usually in areas of poor hygiene and clean water, it is the disease of the poor.

The reason why lepers are confined to colonies is mostly a social one: people are afraid of lepers approaching them, shaking their hands, eating from their food. It is very difficult to catch the disease from lepers, but people see their disfigurement as reason enough to evade them.

Hence, once lepers have settled in the colony, they find it easier to adapt to a life among their own, far from the judging eyes of society.

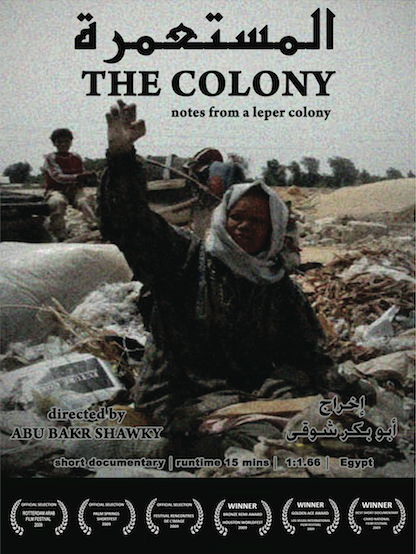

I first came to the colony in 2007 to shoot a documentary about the place that few people knew existed. I had the privilege to interview and follow some lepers to work, between garbage dumps, farms and plastic recycling.

The resulting documentary The Colony was only the beginning of my relationship with some of its subjects, and a few years later I decided to turn the stories I heard into a feature film.

The screenplay for Yomeddine, a road movie about a leper leaving the colony to travel across the country in search for his estranged family, was developed in my final year of graduate film studies at New York University, and is currently in the funding phase (you can have a closer look at the campaign and support the film here).

The film captures the theme that fascinates me most about this place which seemed to be straight out of a work of fiction itself: the struggle of outsiders to be part of a society that does not accept them.

In order to research for the film, me and Zach Kerschberg, a fellow filmmaker and NYU colleague, decided to undertake the same journey, driving along the Nile to the Sudanese border. During the two-week trip we ended up in the most secluded spots by the river, and were both welcomed and chased away by authorities.

It did not help that our drive took place during the third anniversary of the Egyptian revolution (and the security turmoil that comes with it), but on our daily arrests – snitched out usually by the concierge of the one-star province locales we would check in to – I was never able to give police officers a satisfying answer as to why two people were using a car to travel across Egypt, taking pictures of regular people instead of ancient temples and tourist sites.

The concept of a “road trip” has yet to reach our Southern hemisphere. We made it all the way to the border, despite the Cairenes’ warnings about the perils of the trip, realizing that those “dangers” are often clichés stemming from people who have never left the capital.

As Zach said on a walk through the market of Mallawy, “We’re more likely to get shot in Brooklyn than here.” In a way, just as the protagonist of my story tried to defy society’s clichés about his disease, we tried to defy the clichés we Egyptians have about our own country.

Back in the shabby Asyout hotel lobby, I answered, “I think the song has terrible taste. There is nothing artistic about it.” After a moment of silence, the officer shrugged, “They had to record it quickly to be ready for (deposed president) Morsi’s removal.”

After another hour of silence, I was free to go back to my room.

You can help filming Yomeddine by visiting the online fundraiser here. Even though the fundraising goal has been reached, the campaign is still ongoing until Dec. 7 and would appreciate any contributions, shares, retweets and shoutouts. Any additional donations will go directly into the film’s budget.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss Q&A: Documenting the Oldest Culture in Saudi Arabia Before It Vanishes.