Tucked away in the southwest corner of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, worlds away from the gated compounds and shopping malls of the country’s major cities, is a homeland whose once bountiful legacy is on the verge of vanishing.

History itself is threatened as the tribes of the Asir region, roughly one to two centuries older than the rest of the KSA, find themselves dwindling.

In Asir: Sand in an Hourglass, a documentary four years in the making, multimedia journalist Michael Bou-Nacklie spotlights the consequences of the region’s severe demographic shift – before it’s too late.

We chatted with Bou-Nacklie to get the scoop on this fascinating project.

Why is this region relatively neglected?

This region has no oil wealth and has traditionally been agriculturally geared, so major development has taken some time to reach the area.

Why are these tribes considered “vanishing”?

The tribes are in danger of vanishing because of flight to cities from towns and villages from young people looking for education and jobs, leaving many communities with very little population remaining. Usually only the elderly stay, or very young children under 13 years old.

What drew you to Asir’s tribes?

Every family that originates from Saudi Arabia has roots in Asir. When Saudi Arabia was first established, the few tribal groups were scattered across the desert; migrants from Yemen and Asir made up a substantial proportion of the population boom in the 1970’s.

In essence, if the Asir culture vanishes, centuries of history and tradition will be lost to the ether of time. From the tribesmen of Tihama to the craftsman of Abha, there is so much rich culture hanging in the balance, especially given how so much of Saudi Arabia’s history is still relatively unknown.

The country cannot afford to lose such an important part of its identity (or what should form a larger part of it).

What kind of conservation efforts are being made, if any?

Any serious conservation work done in Asir is usually done by locals who understand the consequences of what is happening. Efforts by the government, including the President of the Supreme Commission of Tourism and Antiquies, Sultan bin Salman, have been made, but those are few and far between – not out of neglect, but because there is so much at stake, many don’t know where to start.

Artisan communities have been set up in Abha, which artists like Ahmad Mater have benefited from, giving them a platform to show their work and become noticed. In the documentary, I spoke to several private museum collection curators who have taken it upon themselves to preserve their own history, as well as the history of their towns.

These collections form a large part of what is being looked after but private collectors can only do so much.

What was the biggest challenge you faced when making this documentary?

Logistics were the main issue. Asir is a large region with varying geography, which made reaching some regions difficult. I was able to get access to visit and stay with Tihama tribesman to document their wedding traditions, something which does not happen often if at all, but due to bad weather the river beds we would have crossed over to reach the remote villages were flooded with seasonal rain, making access impossible.

After arriving in Saudi, Saudia Airlines lost my suitcase, which had additional equipment including hard drives, a drone for fly-overs, as well as some extra camera gear, including all my clothes for the trip. Thankfully, I was able to borrow gear from local journalists in addition to my own camera gear, which I always carry with me.

Without the help of my friend and second shooter, Sami Alamoudi of FKAD design, I would not have been able to complete the project in the fashion I intended.

What are some highlights from your journey?

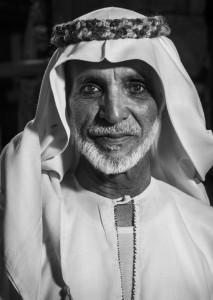

Over the course of recording interviews, I came across Dahdough, a private collector who draws a parallel between food, hospitality and the culture of Asir. This man welcomed us into his home and spent several hours with us discussing the region and how it has been changing with a spirit indicative of the area, full of life and warm welcome.

Mohammad Turshi Almai is another interesting character, an octogenarian who built his own mosque and majlis (gathering area) at 83 years old by himself and using only traditional construction tools and materials. This man is an incredible remnant of people slowly vanishing, embodying the same spirit of the “bedou” Wilfred Thesiger wrote about in his journals. A culture of proud men with a strong sense of duty and honor.

What inspired you to make this documentary? Why Saudi Arabia? Why Asir?

I have worked in the Kingdom for close to eight years and I met Turshi while on assignment for Brownbook magazine back in 2011. I had been trying to get this documentary off the ground when I was in Saudi Arabia but with little success because history still is not something that is highly prized, so many investors did not see the point in recording what is happening in Asir.

Thankfully, Princess Reema bint Saud understood the urgency of what was happening and helped me make this project come to fruition.

While working in Saudi, I made it my mission to show the world the diversity of what the country really is, beyond the news headlines. Yes, it does have a different lifestyle, but buried under those headlines is quite honestly one of the most unique and ornate cultures the world has never really seen.

So much of the country is fast, expensive cars and malls growing out of the ground, selling seemingly the same five things. Places like Asir are almost another world, the very fundamental elements of what makes Saudi Arabia such a rich and vibrant country culturally, originate for the most part from Asir.

When is the documentary launching?

The documentary is launching later this year, the photography book is being produced by the publisher and premieres are being organized in several major cities around the world, including Jeddah, Washington DC, London, Paris and several others.

The book will be published later this year and will be available online at Amazon and hopefully some local distributors like Jarir bookstore.

Give us the scoop on your next big project.

I’ve been working on this project (trying to make it happen for close to four years) and the last year has been spent on editing and producing the final product, but my time with Asir has come to an end, unfortunately.

I am currently working on securing funding to document the exodus of Christians from Lebanon – normally, a minority that controls most of the wealth. Most Christians have been leaving Lebanon because of the more recent political instability from neighboring Syria, but also a growth in extremist elements like Hezbollah have hastened their departure.

Despite this, Lebanon is home to some of the world’s oldest Christian institutions outside of Jerusalem and Syria, so I want to document how Christianity is continuing despite these challenges.

It’s a similar problem Christian communities are facing everywhere – with a loss of the denomination, what makes a church? Is it the people, the clergy or the building itself?

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss “Photo Diary: Inside Umm el Howeitat, Egypt’s Ghost City“.