There is no doubt about it. A presidential election will be held on June 3 in Syria and Bashar Al Assad is going to win. The only question is by how much. Regardless of byzantine debates about whether this vote should take place or not, the truth is that the electoral scenario in Syria could be compared, with a pinch of salt, with the scenario in Egypt. The regime is perfectly capable of rigging the results, but it won’t need to, as a sizable majority of the population is looking forward to seeing the strong man elected.

The main reason for this paradoxical mindset revolves around stability, the scarcest good in the region nowadays. Just like Sisi has promised the Egyptian people he will quell terrorism and will regain economic growth, Assad is also able to allege that he has the wind in his favour. These times, he may well convince his constituency by explaining how the truce in Homs, one of Syria’s largest cities, could be the first step towards his government regaining control of the whole country.

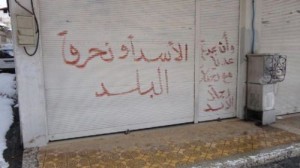

The next objective is clearly Aleppo, currently the rebels’ largest stronghold. His constituency was already well aware of the fact that their country has been plunged for months – and even years – in an all-out war. This is precisely the saddest bit of this conflict: No faction will be able to declare victory if its rivals are not completely routed. Not only members from Assad’s Allawite sect, but also members from other communities and groups – Christians, Druzes, other Shiites, the elite who decided not to pick a side, the rich merchants, public clerks… – are terrified of the prospect of Assad losing the war, for that would mean their becoming targets of all kinds of acts of retaliation and vengeance. The aim is thus destroying everything and everyone on the other side of the battle field. Or, as Assad’s propagandists put it “Assad or we burn the country”.

Assad has also managed to maintain his relationships with his regime’s key allies: Iran, Hezbollah and Russia. Coincidentally, all three seem nowadays stronger than ever and are considered by many the real kingmakers in both this conflict and even from a regional perspective. Assad has also managed to convince both a huge number of Syrians and the international community that he is – as he incessantly pledged to be at the outset of the rebellion – fighting against terrorism.

In spite of numerous efforts from within and from the outside, the rebel side has been kidnapped by a growing number of jihadist groups – some of them coming from neighbouring countries (and even Europe!). Nobody really knows anymore whether these splinter groups are waging a war against Assad or against each other, something that has lead to a deep wariness in the West, for the last thing countries such as the U.S. and France want is to fund future terrorist attacks targeting their own interests.

The bitter truth is that Assad looks nowadays like a credible candidate and everybody in and outside Syria know and recognise many will vote for him. Well, not those who have been killed or have fled the country, but those who are allowed to vote, i.e. those who live in areas under the regime’s control. These are the people who, as I said before, often belong to communities that are terrified of the side-effects of Assad’s overthrow. But these are often the people, from Damascus and Aleppo’s urban middle class, who thrived under Assad’s regime, for the country was enjoying comfortable economic growth before the uprising. It was, of course, an unequal growth which benefited just identified individuals in a country riddled with corruption and clientelism.

Assad will win not only because of the reasons cited above, but also because he would win even if the country were to held free and fair elections. And this wouldn’t be his first time. He was first elected to office, following his father’s death in 2000, with a 99.7% majority. He was re-elected in 2007 with 97.6% of votes in his favour. He will be re-elected in 2014, the year in which another seven-year term has run its course.

These elections are held not because Assad wants to reaffirm its power, nor because he believes it may be a means to put an end to the war, but because the system he and his deep state have been building for years requires them to. Moreover, as an early response to the uprisings, the regime slightly modified the Constitution in 2012, including a commitment to “political pluralism”. What better way to prove this than a vote?

Last but not least, Assad will win because there is no real alternative. Or is there? A fragmented opposition incapable of even showing up in the news every now and them? A Free Syrian Army whose only aim seems to be nowadays fighting the Islamist? Or these Islamists – funded by countries who could not really be defined as democracies (aka as Saudi Arabia, Qatar and UAE) – who have threatened to make Syria – and its world-known diverse multi-ethnical and multi-sectarian social fabric – disappear in their way to create a new Sunni Islamic state in the heart of the Arab world?

Let’s not even speak about Mr. Assad’s presidential rivals: Maher Hajjar and Hassan Nouri, who have belonged to the regime in one way or another and preach Assad’s exact same message (especially concerning fighting internal and external terrorism – the term “global war on Syria” often used by state media) and constantly claim they are merely presidential candidates, not in direct competition with Assad.

In the midst of a bloody civil war, with a death toll standing at 150,000, nine million people displaced and large areas of the country still held by the rebels, many fear these elections could grant further legitimacy to Assad’s regime, that from the beginning treats the whole rebellion as a security rather than a political issue.

The bad news is that the bulk of foreign powers involved in the conflict – both from a regional and an international perspective – already consider Syria more a security and stability issue than an issue revolving on what the uprising was about. Syria went from a peaceful revolution to civil war.

It’s maybe high time for them to take into account the interests of the Syrian people, not those of the regime or opposition. Perhaps the way forward in Syria is not Geneva-style international summits, but locally Homs-style brokered agreements reached by Syrians themselves.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss Discovering MENA: Egypt’s Presidential Elections.