Lebanon is an incredible country teetering on the edge of utter dysfunction. It has been without a president for more than 460 days. It has absorbed almost two million Syrian refugees. For decades, it has suffered widespread power outages. And last year, the very members of parliament tasked with tackling these problems extended their own terms until 2017, continuing to ignore calls for elections and real representation.

In September, when the mandate of the commander-in-chief expired, the minister of defense unilaterally extended the term by a year. Instead of appointing a new chief — as is too often the case in Lebanon — another band-aid was slapped on, procrastinating a problem, instead of solving it.

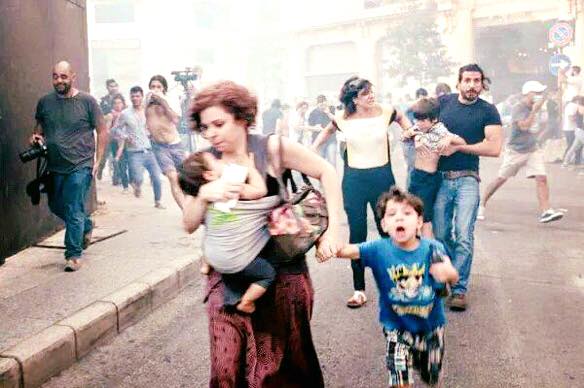

But Lebanon, like many of the protesters in the streets this weekend, is still bleeding. When thousands took to the streets to protest these indignities and raise their grievances, the government — infamous for failing to act — ironically, overreacted.

Riot police and soldiers deployed by the commander-in-chief used tear gas, bullets and batons on protesters, injuring dozens. Only adding to the irony, despite Lebanon’s widespread water shortages, police also used water cannons to disperse the protesters.

But there is reason for hope. The public, which has become rightfully and notoriously apathetic to the cycle of government paralysis, political bickering and factional infighting, has reached a breaking point. The stench of garbage piling up on the streets of the capital during this unusually hot summer seems to have awakened even the most disinterested of citizens to the growing reality that Lebanon’s growing problems are not only an unsustainable tragedy, but may soon be an insurmountable one.

The joie de vivre attitude that many Beirutis have come to live by, boast about and rely on to distract themselves from the unnecessary obstacles of daily life is increasingly threatened by the fact that the problems are no longer out of sight and out of mind. Instead, like the trash piling up on the streets, they are not only visible, but now impossible to ignore. And sadly, the solutions so far are as make-shift as ever. Some residents are burning the trash, municipalities are hiding it in tucked away corners and burying it in empty yards and far too many are hoping the problem will — one day in the not so distant future — solve itself.

As people continue to gather in the streets, demanding that the government resign, others are taking to Facebook and Twitter asking whether the protests and government’s heavy-handed response will inevitably result in a fate similar to that of Syria, Libya, Iraq or Yemen — a failed state. But the more pertinent, more fundamental question is whether there is a state that exists in order for it to fail.

#Beirut downtown preparing for blast walls near govt offices after #youstink protests. #Cairo effect pic.twitter.com/G6Sv97Xm7C

— Sarah El Deeb (@seldeeb) August 24, 2015

Others bicker about which political parties have the so-called “right to protest”, when the real question is why the people, Lebanon’s citizenry — as individuals — are robbed of the right to protest.

This is one of the country’s fundamental problems. People here love to argue, to complain (even expats — and, in some cases, especially expats). But all too often the very basis of these arguments are founded under a false premise built around entrenched political and sectarian affiliations (and the perceptions that come with them), instead of the realities on the ground that perpetuate these all too often inherited perspectives.

Admittedly, I don’t live in Lebanon. So I realize that it is easy for me to say this, but it remains true: All of this energy and time serves only as a distraction.

A sobering reality is now too obvious to ignore: The political elite, while still seemingly somewhat in control, have proved themselves to be completely incompetent. Not once, not twice, but relentlessly.

Still, the argument will continue to be made that Lebanon, despite all the internal and external challenges it faces, has remained relatively secure precisely because of the ruling elite and unique, if somewhat dysfunctional, sectarian power-sharing system. They’ll say the regional climate and neighboring circumstances make it too fragile a time to challenge the status quo. Sure, the politicians are corrupt. Sure, they don’t solve problems. They’ll say, look at Egypt, there security trumps freedom. Security trumps dignity. Security trumps humanity. But that argument is as corrupt as the leaders themselves.

Mocking the absurdity of Lebanon’s politicians and complaining about corruption has become a national past time. But if we are to learn from the lesson of Egypt’s revolution, we should ask what would happen if the new generation was able to organize to become the politicians, all while challenging them in the street simultaneously?

It is impossible to know what will come of this moment in Lebanon’s history. It is impossible to tell whether this is the beginning of a revolution or another blip in the ongoing post civil-war devolution. Because when Lebanon is in the news, the focus is always on its role as a survivor — and it is true. It has “survived” the Arab uprising. It has survived the war in Syria, and the refugees straining its economy. It is surviving the Islamic State and the threat it poses to its security. Lebanon is undoubtedly surviving, against the odds. But what if, instead of surviving, Lebanon started thriving again?

Admittedly, I’m not Lebanese. But like many people who spend a lot of time in the country, for as much as I complain about certain things when I’m there, I happen to be in love with Lebanon. I also happen to be a dreamer and I know enough young Lebanese dreamers to still hold on to the belief that this could be a pivotal moment of transformation, without feeling completely naive in this convictions. From my limited, though intimate experience with Lebanon, I’ve learned that the paradox of life here is that it can be everything and nothing all at once: as depressing as it is enchanting, as resilient as it is resigned.

On Sunday, Lebanon’s prime minister made a promise — that members of the security forces will be held accountable for the violence against protesters.Yet, while protesters languish in jail cells, nothing has happened to the security forces that attacked them.

Of course, much like the disappointment that we’ve all felt from a lover’s broken promises, Lebanon’s leaders have left us all in despair too many times. Put simply, the government here is all talk, a bit of torque, but no action.

So while it may be true that you can’t choose who you love, what you can choose is how to react to their disappointments. You can keep asking them to change, or you can change yourself, and in doing so, change your circumstances.

As Ambassador Fletcher reminded us with his parting words: “I believe you can defy the history, the geography, even the politics. You can build the country you deserve. Maybe even move from importing problems to exporting solutions. The transition from the civil war generation lies ahead, and will be tough. You can’t just party and pray over the cracks. But you can make it, if you have an idea of Lebanon to believe in. You need to be stronger than the forces pulling you apart. Fight for the idea of Lebanon, not over it.”

I couldn’t agree with him more. #طلعت_ريحتكم #YouStink #DemandDignity

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss Q&A: Ahmed Shihab-Eldin on Media, Democracy and Social Change in the Middle East.