Image at the funeral of the victims of The Alexandria Church Bombing, April 2017.

A few days have passed since the horrific church bombings that took place in Egypt’s Tanta governorate and Alexandria governorate. Accordingly, it is now time for a sober reflection on the question of fighting terrorists. This question is one that Egypt has been asked and forced to answer.

Firstly, there seems to be an understanding that fighting terrorism is confined to fighting terrorists: using weapons and hard power, to gain control over the use of force within the Egyptian state’s borders.

Whilst this security-based approach is necessary, it is simply insufficient. Terrorism and extremism are ideologues that can and do in fact strongly exist in Egypt outside the bodies and minds of terrorists and suicide bombers.

Image depicting Egyptian police officers stationed outside the Alexandrain Church effected by the bombing, April 2017.

Photographer: Ahmed Khaled.

From people who will not buy items from a store because it is owned by a Christian family, to people who believe that Christians should be barred from certain career paths to people who cheer on such bombings; prejudice and extremism exists everywhere around us.

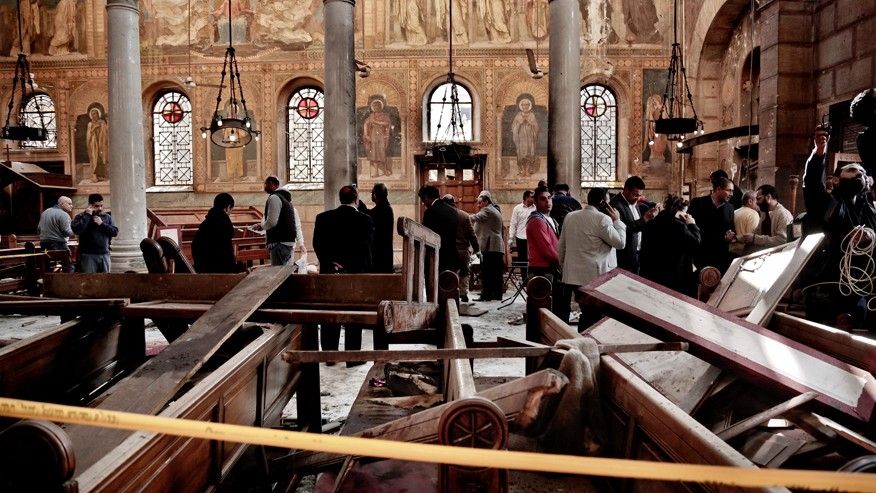

Image depicting Egyptian law enforcement in the aftermath of The Tanta Church Bombing, April 2017.

It is simply no longer far-fetched to claim that for every suicide bomber killing Christians, there exists hundreds of Egyptians who at least share some version of the extremist ideology that led the bomber down this path.

These people should not be targeted merely because they are ticking time bombs that may at some point commit physical acts of violence or aggression.

Rather, they should be targeted because holding these views is already as equally dangerous as detonating an actual bomb.

Image depicting The Botroseya Church Bombing in Cairo, December 2016.

This phenomenon is not confined to holding views towards other religions. It is something we witness in several forms, from opinions on gender roles to debates over public morality codes to opinions on who counts as a proper Muslim.

Image depicting the aftermath of the Tanta Church Bombing, April 2017.

Secondly, targeting these critical factions of mass-society does not mean imprisoning them. It means creating an alternative counter- discourse that has the power to rationally counter religious extremism, using its own language.

In other words, we need open public debates and forums, where the language of religious extremism is logically met with a moderate version of Islamic ideology.

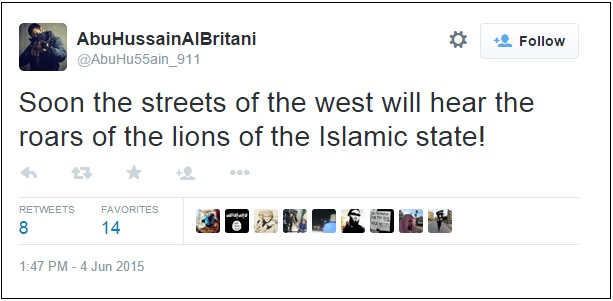

Thirdly, institutional and mainstream understandings of the terrorist profile need to change. While social class and level of education likely acts as indicators of any given individual’s predisposition to becoming a terrorist, terrorists no longer have a definable name, face, culture, level of education, social class, political background, personality trait and/or country of origin.

And if this is true for terrorists, then it is especially true for those who hold extremist views but are not terrorists per say.

This point is especially true with the widespread use of the Internet, and social media platforms. The problem, however, is that no action has been taken to reflect any serious effort to study terrorists, and people who hold extremist values, in a sociological and/or psychological way(s).

Finally, no serious organized efforts exist to document the specific and nuanced ways in which the extremism of Wahabi-based articulations of Islam has influenced mainstream Egyptian culture.

Indeed, these radical Wahabi-based articulations are not only responsible for a wave of terrorist attacks that occurred in Egypt between the 1990s and early 2000s and re-surfacing now, they’re also responsible for a general and overall radicalization of every day Egyptians.

Image showing the coffins of those slaughtered in a 1997 terrorist attack on Luxor.

Image showing the aftermath of Ghazala Gardens in Sharm El Sheikh, 2005.

With several regime changes, presidential changes, a revolution, and countless constitutional amendments, one fact has held true for Egypt over the past 25 years or so: Extremism has become a commodity for mass consumption, and nothing comprehensive is being done about it!