Buzzwords and terms like sustainable cities and the green transition have been thrown around and used ad nauseam in articles and conversations in the run-up to COP27 being hosted in Egypt’s Sharm el-Sheikh, but what exactly do these terms mean? And is the vision of a green future for cities like Cairo in hotter climates and developing economies the same as cities like Paris with more moderate climates and developed economies? CLUSTER, a Cairo-based platform for urban research and design initiatives, has for over ten years been trying to find the answer through research and experimentation that puts the local community first. With that in mind, we sat down with CLUSTER’s co-founder and architect Omar Nagati to learn more about their vision.

At their office in Agouza, Nagati described the organization as an “independent urban design and research platform that started over ten years ago with a group of architects, urbanists, and people that are working in the social sciences and arts that are interested in cities and the use of public space.” However, unlike architecture firms that design whole new districts in desert cities or the allure of mega projects that want to demolish areas and start again, CLUSTER experiments with incremental and small changes in the existing city as a solution to wider problems.

Will the Green Arab City of Tomorrow Actually be Green?

The conversation around the need for sustainable cities and the green transition in the public imagination paints an image of rolling green fields of grass and verdant greenery emerging out of cities. However, unlike a Google image search for the term ‘sustainability’, which reveals lush greenery and seedlings hatching out of moist soil, the future of sustainable cities and the green transition in Arab nations will need to be very different according to CLUSTER.

Unlike other countries presented as examples to follow for a green transition, the Arab world has an incredibly hot climate that often decimates crops in places like Iraq and Syria. Likewise, the region has a serious issue of water scarcity in which 90% of children live in areas of high water stress and a lack of arable land, which in countries like Egypt only accounts for 4% of the country’s total land mass. Considering this, the idea of green fields emerging out of the desert is the exact opposite of sustainability and the green Arab city of the future will necessarily be very different from cities in Europe and North America. However, while the future of sustainability in the Arab world may not be green fields, CLUSTER has been working on its own model of sustainability for Arab cities to be excited about that suits the economic, social, and environmental conditions while still promoting inclusive public spaces for all to enjoy.

Explaining this disconnect with the image we have in our heads when we speak of a green transition and sustainability and the reality for places with hot climates and developing economies, Nagati described how “Some of the international standards, including the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, are developed in a way that is based on the experience of mostly North America and Europe.” Instead, what CLUSTER has been trying to do is “to find a way to translate and integrate these very abstract principles on the ground, starting with how people area actually developing their own neighborhoods and to try to work with them to bring up a little bit towards this goal.”

Learning from the Past

For CLUSTER, creating a new model for sustainable Arab cities means looking to the past for ideas just as much as looking to the future with new and ingenuitive ideas. Nagati pointed to already existing ways that cities in the region have dealt with hot climates and run on a more sustainable basis in more traditional and also in newer informal neighborhoods. Pointing to how the future of green cities in the Arab world may look different in colder climates, Nagati discussed how “our cities have historically been developed as a denser urban fabric, but using courtyards and narrow streets because shaded spaces generate natural ventilation systems between low pressure and high pressure. You can look at courtyards, backyards, backstreets, and the network of gaps through the fabric to develop an alternative way to address climate change”. It is from these observations and others that CLUSTER is trying to piece together a new model for urban areas to deal with the increased temperatures that come with climate change through careful experimentation with local communities.

Instead of large exposed areas of grass that need constant watering, Nagati pointed to the use of courtyards in Arab cities that historically have been able to provide a form of public space. The courtyard is an iconic part of Arab architecture that has seemed to almost completely disappear from modern urban planning in the region, despite the fact that it served a particular purpose in the Arab world’s hot climates. By offering shade to both people and plants, courtyards provide a cooler microclimate for people and for plants to grow without the need for constant watering, but also a communal space that has historically been used just as much for socializing as for trade.

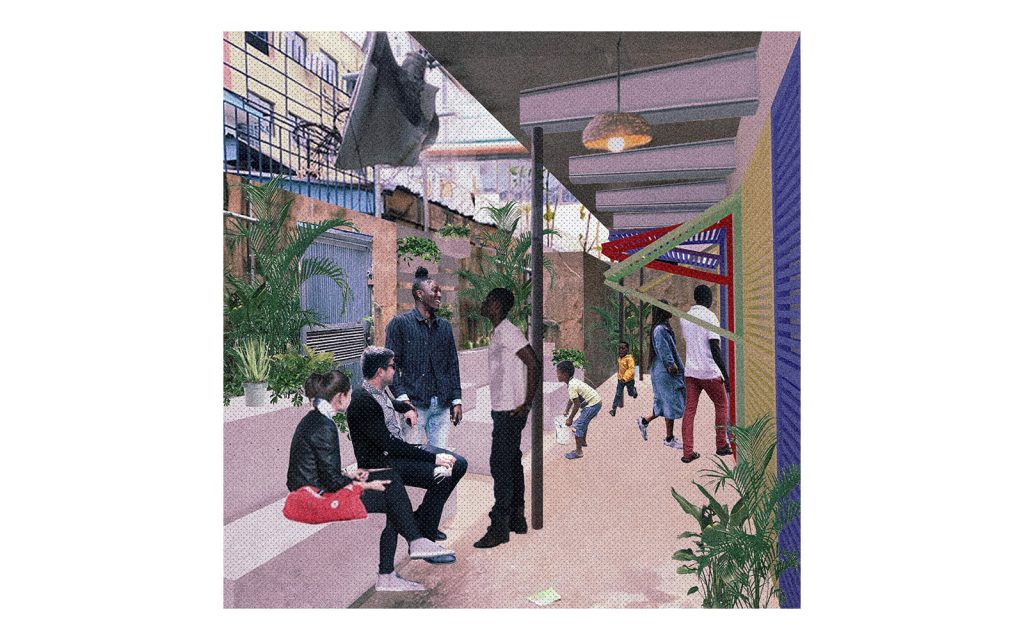

With the need for green public spaces expressed as a priority by governments across the region, projects like Green Riyadh as part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 forgo the creation of public courtyards in favor of large parks. CLUSTER, however, conducted several projects throughout Cairo in which they reimagined alleyways as communal courtyards by planting trees suitable for the environment and proving to a seat. One of its projects in Downtown Cairo’s Kodak Passageway beside the restaurant Eish & Malh and the Al-Adly synagogue has stood the test of time and remains a rare public space in central Cairo enjoyed by all.

Often mistaken as simply an indicator of overpopulation and urban poverty, density in Arab cities also presents a form of city layout that developed over the centuries as a way to control temperatures and create more liveable environments, according to Nagati. The now much frowned upon narrow streets that make the historic urban centers of the Arab world and also newer informal settlements actually create much cooler microclimates and shaded routes so people can walk and cycle between places. Newer settlements in the desert, on the other hand, with wide streets and individual buildings spread out along vast areas make the car the only option to get around due to the sunny and exposed roads and long distances between places.

Building on the idea of how dense urban areas can utilize shade and proximity to create more liveable and enjoyable neighborhoods, CLUSTER conducted several research projects and architectural interventions in informal areas. In one of these architectural interventions typical of CLUSTER, which similarly took inspiration from more traditional forms of Arab architecture, they experimented with large fabric covers to provide shade for a street market in an informal area of Cairo. While promoting a cooler microclimate, the project also had a great social value, claiming areas of the street as communal areas for people to gather.

Working with the Community

Following their philosophy of small-scale and affordable interventions to create more sustainable and liveable spaces, these architectural interventions are also presented as models for others to follow. However, more central to CLUSTER’s philosophy is the importance of community engagement and an expanded idea of sustainability that includes economic and social factors.

CLUSTER’s programs and operations manager Youssra Zakaria emphasized that central to all of their project’s success was the support and involvement of the local community in their projects. Looking back at which projects were successful and those that often fell into disrepair shortly after their implementation, Zakaria drew a clear line between those that were developed over a lengthy period with the local community and those that were created with less cooperation with the local community. Nagati similarly chimed in “You can plant all the trees you want, but unless people have a sense of ownership and have brought into this idea, this idea is not sustainable.”

The future of sustainability and green cities in the Arab world will look different from much of the rest of the world, but it’s a future nonetheless with exciting possibilities. Through CLUSTER’s experiments in cities across the Arab world and Africa, we can get a glimpse of what this future may look like.