Hopes deflated and dreams shattered, a young Ahmad Abdalla’s ambition of becoming a filmmaker came to a rapid halt. Rejected by the Film Institute twice – each year the institute picks only eight new students – and surrendering to his parents’ pleas, Abdalla enrolled at the Music Institute to become a viola [A bow string instrument that is slightly larger than a violin and has a deeper sound] player.

Nonetheless, he was unable to suppress his dream of becoming a director and started dabbling in the world of filmmaking. He always knew that despite his love for music, he knew that he was not meant to be a musician. He belonged on the set of his movie.

A self taught non-linear editor, a rare skill to have back in the early 2000’s, Abdalla soon became the youngest and one of the most sought after editors in the world of filmmaking. Eight years and ten commercial movies later, Abdalla was ready for the change of a lifetime, the transformation that turned him to the successful director he is today.

With three highly acclaimed feature films – Heliopolis (2009), Microphone (2011) and Rags and Tatters (2013) – under his belt and a shelf embellished with prestigious awards from the Carthage Film Festival, Montpellier Mediterranean Film Festival and Istanbul International Film Festival, Abdalla is at long last exactly where he wants to be.

An avid supporter of the arts and music scene, Abdalla has recently joined forced with Red Bull Egypt to create Handstand, a documentary, which brought to center stage the vibrant, thrilling and often challenging life of Egypt’s B-Girls and Boys.

How did the idea for ‘Handstand’ evolve?

We came to the idea together. I know the people at Red Bull Egypt and I was always telling them that I wanted to do something that focuses on the music scene and if they had any ideas, they should let me know. And this is how the idea of creating this documentary came to be.

I hardly knew anything about the B-boys and their world seemed very interesting. So, I agreed to go meet them [b-boys] and see what can come out of this idea. I was pleasantly surprised to see dancers, both young men and women, practicing out on the streets all over Cairo.

When did you start working on ‘Handstand’?

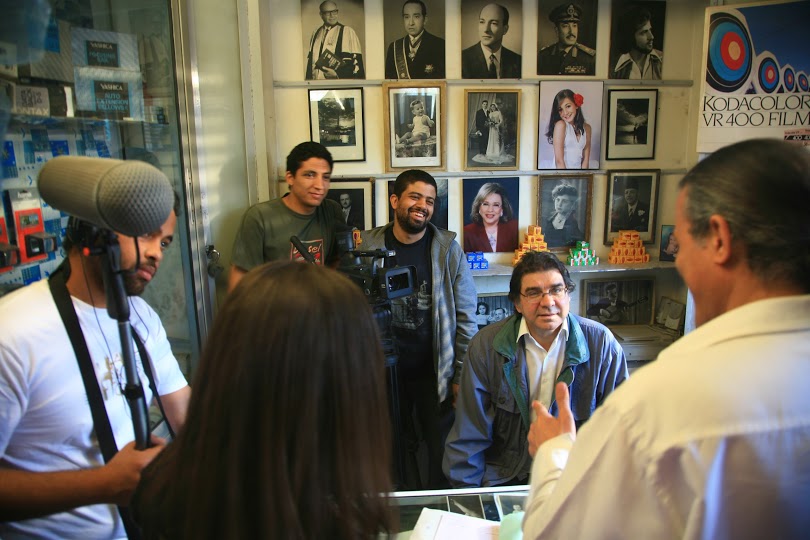

All of 2013… Sometimes we could not shoot in certain places and at certain times, because of last year’s turbulent times and happenings.

What was the biggest obstacle you faced while working on this project?

The same thing I’ve been facing when working on any movie post January 25 Revolution is peoples growing hate for the camera.

For example, when I was shooting scenes for Microphone back in 2011, my crew and I were welcomed with open arms. During one of the shoots, someone from the audience’s phone rang, interrupting the shoot, so when we asked the crowd to put their phone on silent so as not to ruin the shoot, everyone willingly abided. There was obvious cooperation.

Shooting again in the same place, but only two years later, I was shocked to discover how our reception there had differed. From the moment we started setting up our equipment, people became vicious and were pushing us back into the car and dubbing us traitors from the despised Al Jazeera channel.

How did you pick out the B-boys that were featured?

Red Bull helped me a lot honestly, especially because they have been organizing this competition [annual break dancing competition for Egypt’s top B-boys] for three years. I wanted to sit with them, get to know them. Some were very young, ages varied from 17 to 31. I started meeting up with the B-Girls and B-Boys in early 2013. I didn’t just want to film the good ones that compete; I also wanted to show the nitty gritty details of their lives, practices and families.

Were you following a written script or was it spontaneous?

No, I did not work with a script, I worked with what I call a backbone and I let things develop as we go along. We were working in a workshop-like atmosphere.

Was there something you wanted to include but couldn’t?

I don’t like saying that I couldn’t do something, but I think if it were easier for me to shoot out on the streets, the end result would have been better. More freedom would have made things turn out better definitely.

The documentary making scene in Egypt is…

The revolution has definitely played a role here. Suddenly, so many films were being posted on YouTube, regardless of quality. This promoted the idea of creating documentaries and now even newspapers started making their own. So, yes, I think that things are moving in the right direction.

Where do you see Egypt’s filmmaking industry? What does it need to help move it forward?

I think that we are definitely on the right track. We now have a pool of talented directors, actors and cinematographers, who are succeeding in creating new and good movies, and there is a growing fan base for such movies. I’m very optimistic.

What is next for this director?

I just finished shooting my latest movie, Décor, and I’m currently in the final stages of its editing. The movie stars Khaled Abou El Naga, Maged El Kedwani and for the first time in a serious role, Horreya Farghali. This is the first time I’ve directed a movie that I hadn’t written; it is written by director and scriptwriter Mohamed Diab (678, 2011). It is a black and white psychodrama and has nothing to do with politics. I’m still unsure of its exact release date.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss our interview with Director Amr Salama.