In his two-part play ‘This Flesh Is Mine’ and ‘When Nobody Returns,’ Brian Woodland manages to bring together Homer’s Troy and today’s Palestine. The play integrates some Arabic singing and talking, when some characters are at their most exposed, to the classical lyricism of Homer’s poems.

The geeky side of us got curious about how on earth the classical Greek writings of Homer, arguably the greatest of all poets – author of epics The Iliad and The Odyssey – mixed with themes from one of the longest lasting current conflicts – the Palestinian struggle – sound. Hence, we sat through the whole performance and then had a chat with the Palestinian and British cast and crew during their London run.

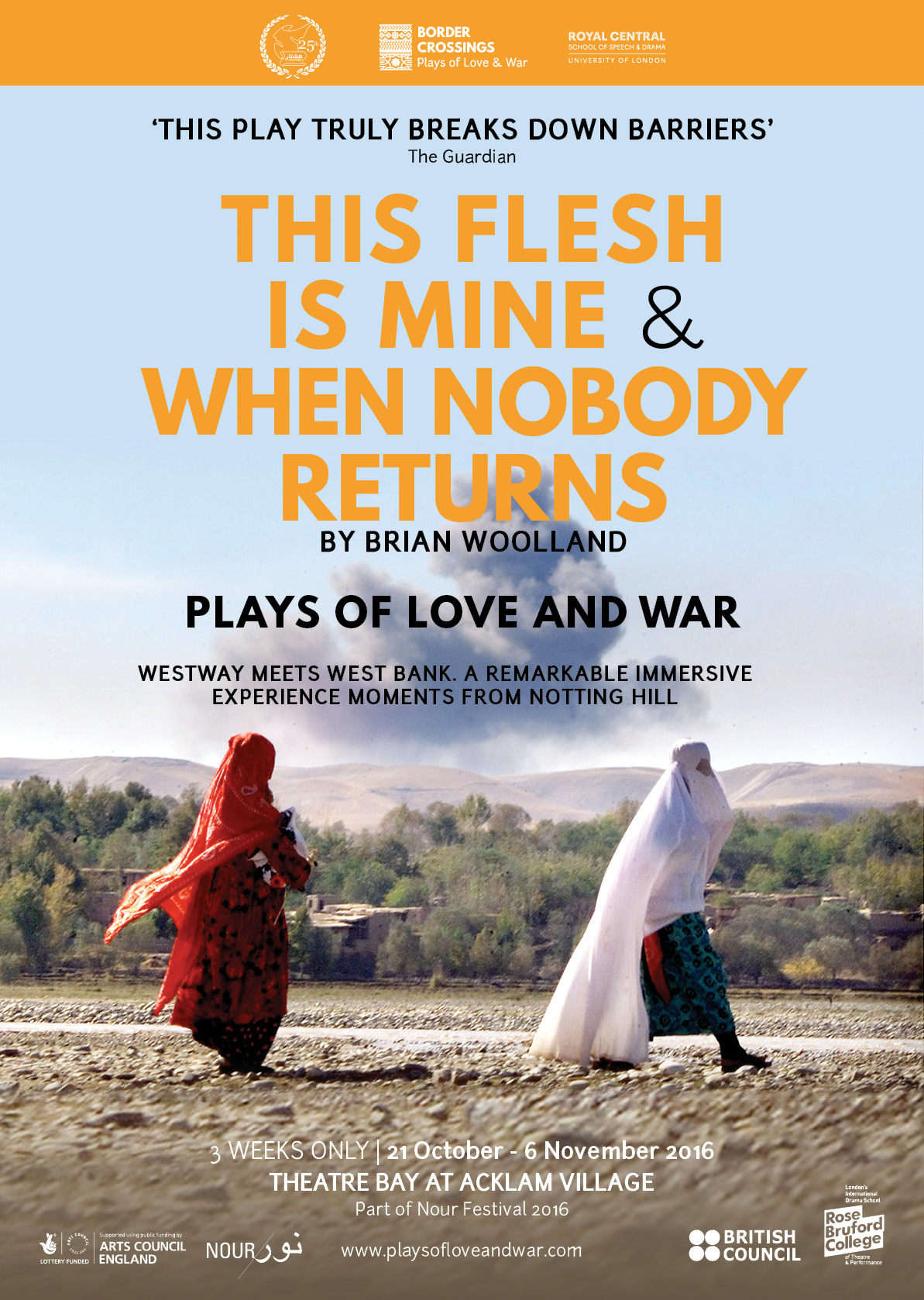

Palestinian actress Bayan Shbib feels that this play is “tackling our world, the Middle Eastern world, or countries that are struggling for causes and trying to echo that in classical theatre world.” In fact, themes of land, occupation, post-war trauma, soldier’s reintegration, grief, overstatement of the truth during conflicts and homecoming definitely resonate loud in a theatre near Notting Hill where the play is performed until the 6th of November.

Iman Aoun, who plays Penelope, founded Ashtar in 1991, a theatre organization in Ramallah with branches in the West Bank and Gaza that offers four-year degrees to young people, community plays, and professional theatre like this one. She tells us it’s their role as artists to contribute to how the story is told. “Homer had already presented the poem then,” Aoun says, “but now it’s our turn and it has to be with a take on what is going on in the world, otherwise it would only be archaic.”

“The reason for doing it through mythology is it avoids the pettiness of a lot of the modern political discourse” Michael Walling, the director and founder of Border Crossings adds. Walling argues the Greek plays are a great model to get to “a larger truth” where no matter where the audience comes from it can “get to a sense of what it actually means to have that, to lose that, what it means to long for something that is absent, what it means to be caught in endless cycles of violence and retribution even when you’re trying to get away from them.”

Co-produced by UK-based Border Crossings and Palestinian Ashtar, the first part of the play was already performed in Palestine and London two years ago and due to its success is now getting its second round with a new part. Director Michael Walling tells us that the first time they worked on this, two actors out of three got their visa rejected for the London performance, so this time they planned way ahead and managed to fly two actresses out of Palestine for it.

Walling tells us it wasn’t necessarily planned that the two artists to fly from Palestine would be women, but that “[it] is a very feminine play. It’s about belonging in space, possession in space and land and the use of the weaving as a metaphor for remaining in land and natural resistance, which is very much the power of the women in Palestine.”

On the other hand, the British cast and crew were all able to fly to Palestine to rehearse and perform ‘The Flesh is Mine’ in Ramallah. As you would expect, one of the actors, David Broughton-Davies, tells us, “it’s changed my world.” He adds, “I’d worked in Israel previously and I thought I knew a little bit about the region. I knew nothing.”

Broughton-Davies could talk to you about Palestinian dance and films (which he liked to watch without subtitles) for days. “I’ve now got a new set of friends that I will have for the rest of my life who only happened because of this play and the fact that we went there,” he tells us.

Watching the play, we couldn’t help but enjoy the unusual mixing of acting genres between the rather British way of acting and the Arabic style. “The music is different in their voices, that’s good. Because you hear a different energy in the space from them,” Walling explains.

WE SAID THIS: You should also check out 12 Palestinian Films That Will Open Your Eyes.