“If I had known there was such a thing as Islamic Calligraphy. I would never have started to paint. I

have strived to reach the highest levels of artistic mastery, but Islamic Calligraphy was there ages

before I was” Pablo Picasso

Written first in Kufic style, the emergence of the Quran in the 7th century was directly associated with the rise and rise of Islamic Calligraphy that was the primary means of propagating Islamic religion for centuries, consisting of six famous styles among which are Naskh, which is the current style of the Quran, Thuluth, Ruqaa, Diwani, and huge variety of other regional styles including Persian, Urdu, Turkish, and Chinese.

Proceeding the established existence of printing, the relentless advent of the machine, followed by

artificial intelligence and visual edits softwares pose themselves either as a threat, non-threat, or an

irrelevant agent to the longevity of Islamic calligraphy.

In Egypt, under the supervision of the Cultural Development Fund, around 70 Arabic calligraphy schools

are operating across the country as an extension to state schools. The most famous of those is Khalil

Agha School established over a decade ago during the reign of King Fuad the First. From these

schools, thousands of students graduate every year and become practicing calligraphers.

Calligraphy at the Heart of Al Moez

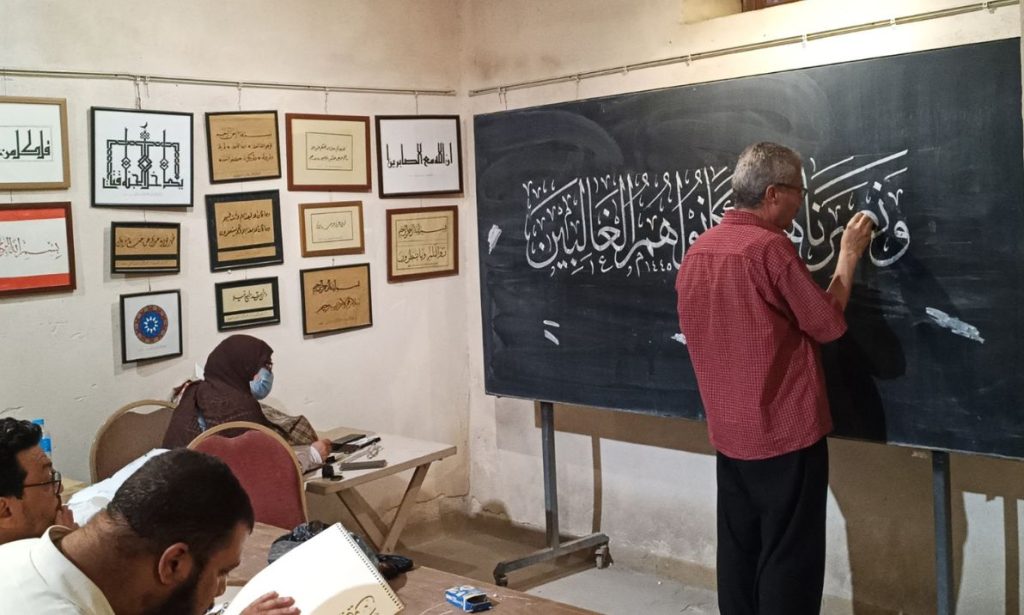

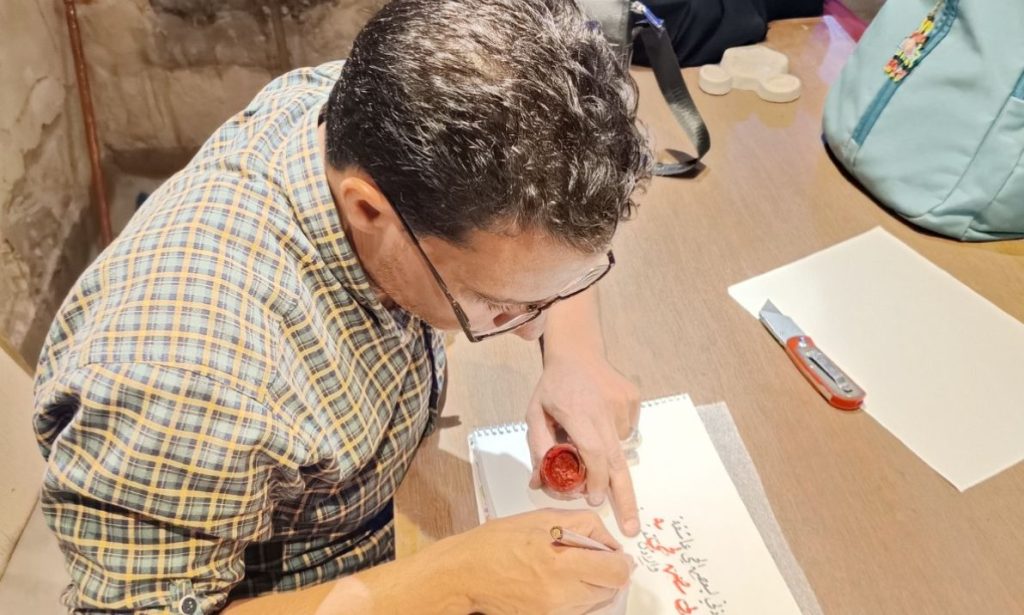

The Sheikh of Calligraphers, Khodeir, runs a privately held school named after him located in Beit

Al Suhaymi, one of Al Moez street’s gems. Around 30 students, differing in age, interests, and

religious affiliations, graduate from this school every year, with an advanced knowledge and

proficiency of the many styles of Arabic calligraphy. Surrounded by a spiritual and historical

ambiance of Al Suhaymi, the students huddle in the two class-room school bent over their white

sheets with enthusiasm, decorating it with ink in equal zealousness.

The walls covered in paintings, the graduation projects of students, smelling of ink and the whirling

dust of colorful chalk. In this relatively small school, observation and imitation of the masters rule,

humble silence prevails, art is embodied and incarnated, and not a trace of technology on sight.

Wafaa Khairy, a calligraphy student in the middle of her first year at the school and expected to

graduate next year said ” I am here out of mere passion, I don’t plan to earn money out of this skill

but it’s needless to say that Islamic Calligraphy despite the intervention of laser prints remains

integral to other arts like accessory making, architecture, and wood carving, it thrives as long as

Islam does.”

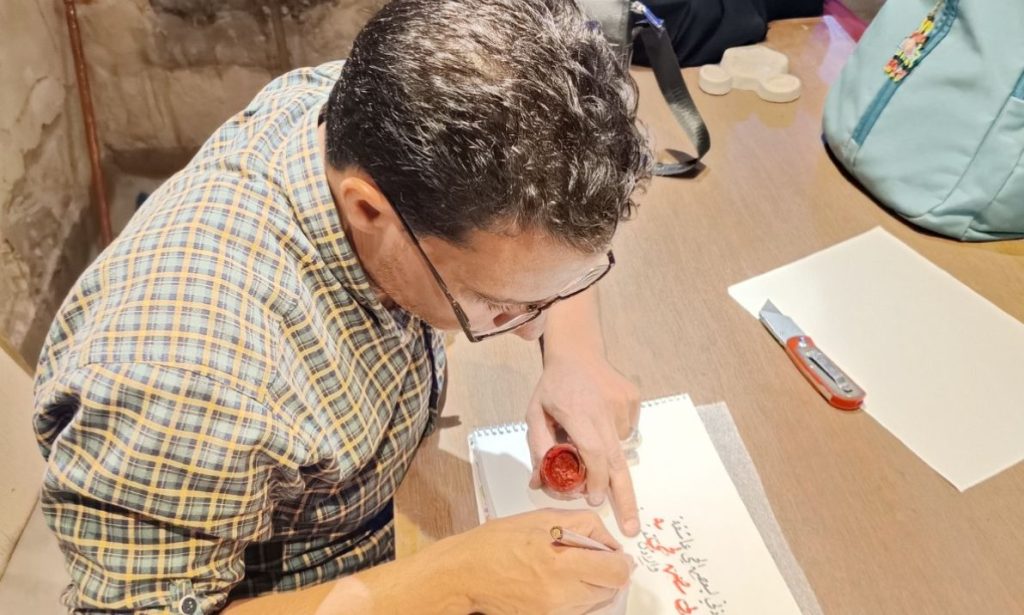

Similarly, a licensed internationally acclaimed calligrapher and calligraphy teacher, Hussein

Mokhtar, believes that this intertwining of calligraphy with many crafts and professions is one of the

main reasons why it can never be lost to artificial intelligence or technology in general. “

Calligraphy came to me by inheritance from my brother, ever since I was a kid in primary and

elementary school, I used to practice it. I would say technology is not a threat to calligraphy since it

is already deeply related to many other crafts and to this day the machine couldn’t outsmart what

calligraphers are capable of.”

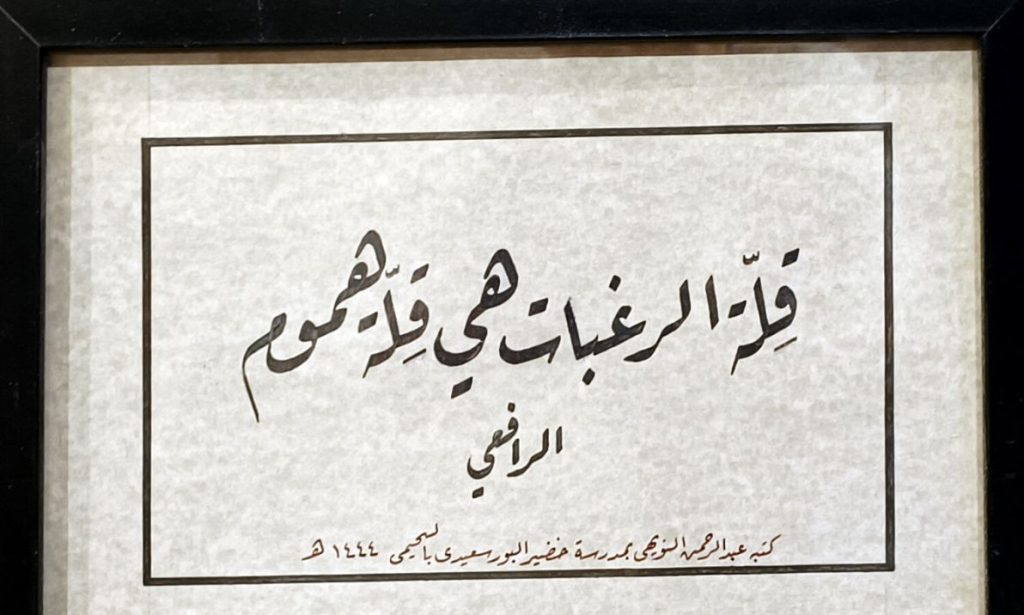

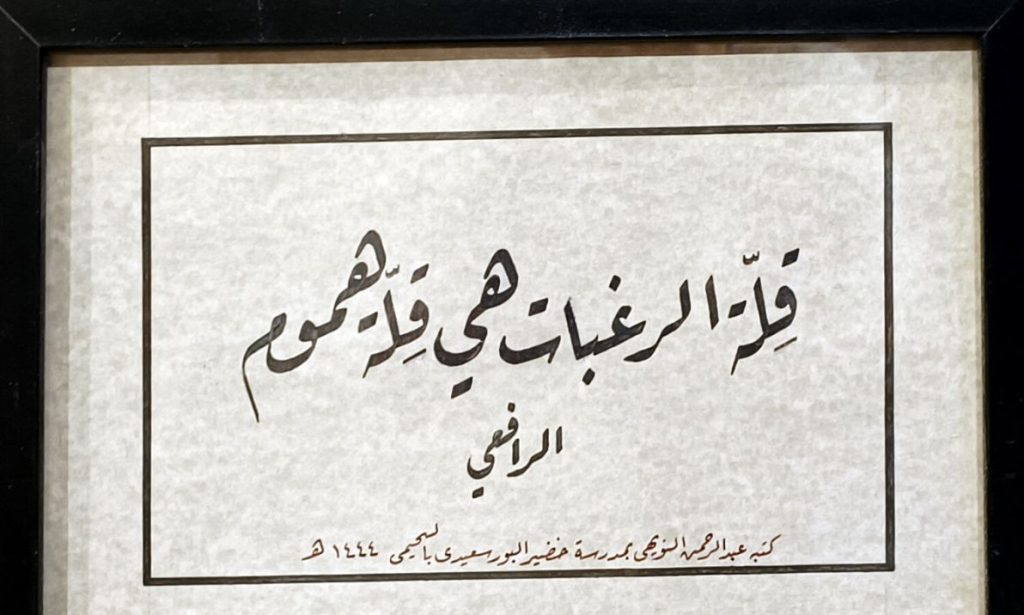

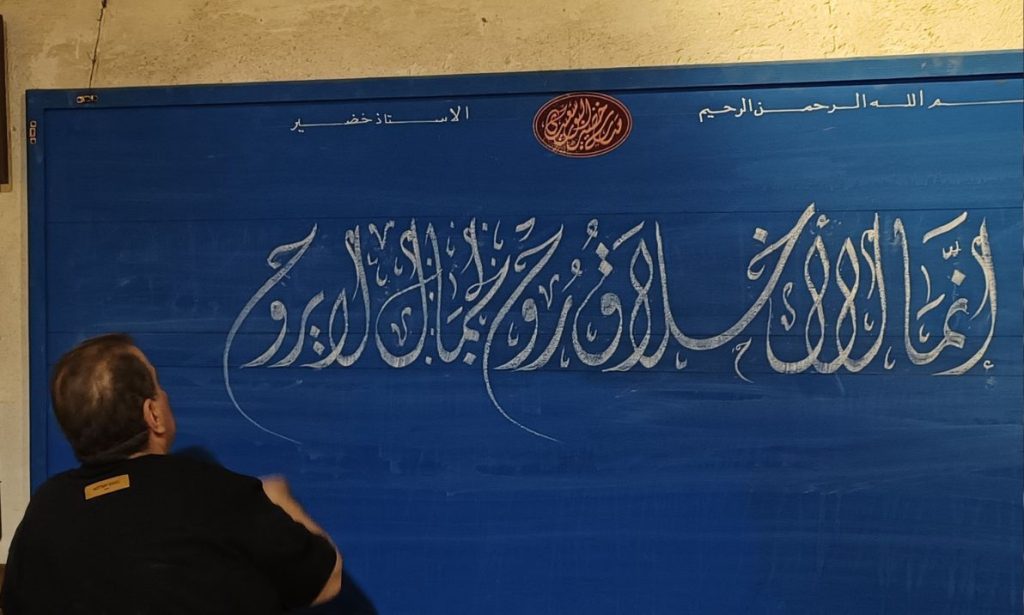

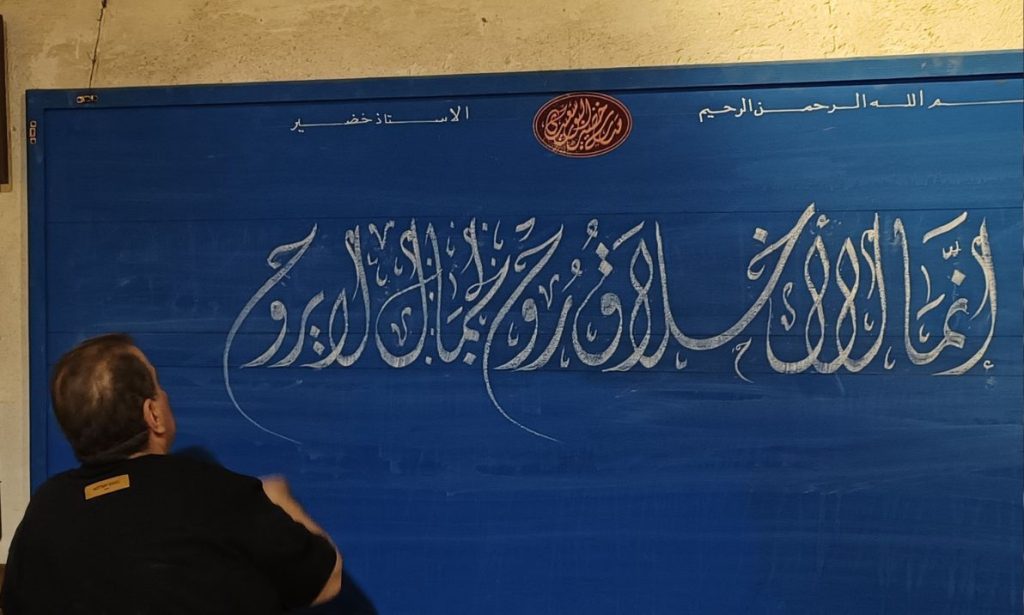

Another acclaimed calligrapher and teacher at Khodeir’s school, Mostafa Al Aemary said

“Calligraphy is subjective and sees its importance in the moment. Anyone can stay up to date with

technology, but you don’t judge them by that, you judge the artist by the original handwritten work.

Calligraphy is a live art born in and out of the moment.”

The pure tangible obsession in Khodeir’s school mixed with the strong belief in the longevity of

calligraphy and its divorce from the financial aspects can be considered a faint trace compared what

is present in Khodeir museum that’s full of calligraphy paintings almost to its entirety.

Khodeir’s Museum: Where Art is not for Sale

Throughout his career, he has painted over 15, 000 art pieces. Khodeir’s museum is not only popular

among his students but rather receives international visitors from all over the world.

He denounces the fetishizing and monetizing of art in his complete rejection to sell it. All over his

huge gallery there is a sign that says ‘nothing here is for sale, not for any amount whatsoever’. When

asked about this, Khodeir said “I can’t stand to sell my art to someone just to leave it hanging on a

wall”. For him, money and art are not related unless inversely proportional.

“The first six years of my life were defining, they made me who I am, and I live by the values I

acquired during this age”. As a child, the sheikh of calligraphers acquired knowledge of Arabic

calligraphy by God’s blessing and therefore he sees it unethical to demand money in exchange for

something that he sees a gift from God, therefore his tuition free school, his literally ‘priceless’ art,

and his leading of a humble life.

“Whoever comes to visit me with a gift, I return it with a better one” Said Khodeir, and infront of

him a closet filled from top to bottom with honorary prizes from all over the world, a sign of a

lifetime of achievements and international acclaim.

Realistically, Khodeir thinks Arabic calligraphy is deteriorating. Although he acknowledges the

longevity of this art, he sees the irony of today’s substitution of the human factor. “Today they have

a name for someone who works on fonts when the computer is broken, they call them ‘computer

backup’, when it should be the other way around.”

“In the past, black letters were drawn on a white background of a doctor’s clinic sign, a metaphor to

his white scrubs, and vice versa for a lawyer’s sign to refer to his black robe. Now a clinic’s sign is

bombarded with colors, and unmeaningful graphics devoid of metaphor”, “I exclude doctors with

such signs and pick the ones with the classic signs, it tells so much about a person.”

In countries like Turkey and Iraq, master’s and PhDs in Arabic calligraphy are given, that’s not the

case in Egypt.

The good news is that, according to Khodeir, these programs are worth nothing

compared to the license given to scholars in Egypt. A license or ‘Ijaza’ is not an easy task and “many

of those who finish their post grad degrees abroad come to Egypt to get their license.”

Khodeir’s school manager, Mohamed Saad pleads for more attention from the government regarding

calligraphy schools “our voices need to be heard, both with regards to canceling the tuitions, and to

enhancing the overall conditions of the schools”

Current Concerns and Future Aims

Although calligraphy schools in Egypr only require a minimum of an elementary school degree, and

an Egyptian citizenship, recently there has been demands from Khodeir to regain its tuition-free

education that attracted students from diverse backgrounds.

” Now the fees are 250 to 300 per year which not only burdens the students, but also the teacher,

whose salary now depends on the number of enrolled students, and this is unacceptable. If one

thing, I wish these fees to be canceled, and students can join the free classes once again” Said

Khodeir, stressing the negative consequences of increasing the fees by 300 percent.

And when Khodeir was asked about his predictions for the future of calligraphy in Egypt, this was

his response: ” I would be a failure if I said I was not optimistic, of course I am optimistic, and

wonderful things are happening soon. This year there are four new schools opening in Hurghada,

Ismailia, Beni Suef, and Minya, as well as dedicating classes for the complete beginners.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t Miss…In Pictures: A Journey Through the Clay Pottery Craft in Old Cairo