The name Mohamed Elshahed has popped up in several places over the last few years. Be it on the cover of a newly published book about modern architecture in Cairo, on the curator’s blurb of an exhibition with the British Museum highlighting modern Egyptian design, or on issues of Cairobserver, a now relatively dormant but still important voice in the world of visual and architectural culture in Egypt and the wider Arab world. As a critic of the hyper-specialised world of work, Mohamed would oppose my categorisation of him as a historian of Arab modernism with a specific focus on architecture and design, and also maybe take issue with my use of the term modernism. Mohamed, on the other hand, described his professional status to me by explaining, “I do history, I write history, I of course studied architectural design, but I don’t design. I curate exhibitions, I work on design exhibitions, architecture exhibitions, and material culture exhibitions.” What at first seemed to me to be an oddly vague and evasive response, became clear as I understood Mohamed’s wish to avoid the straight jacket of academia, the conventions and tropes inherent in many fields, and his wish to reach a wider audience.

Mohamed described how his core interests and focus have remained relatively constant, explaining that, “Since I was a kid, it was really about observing and understanding my environment.” Expanding on this, he told me that what brings all his interests together, “is an attempt to understand the complexity, the physical complexity, and materiality of our physical environments” in the framework of cities. This city, more often than not, is Cairo.

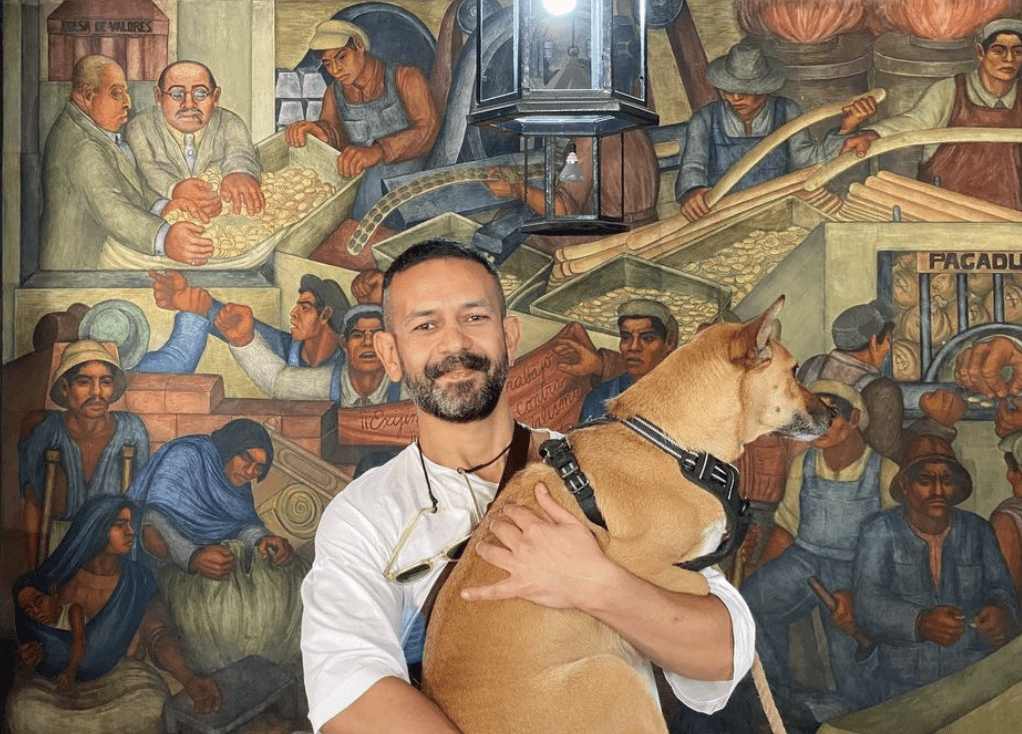

Shortly following the Egyptian revolution of 2011, Mohamed who had just moved to Cairo to pursue a PhD launched a blog called Cairobserver that discussed the physical environment of the city and how its residents engage with it. Building on the hype surrounding blogging at the time, Mohamed intended Cairobserver not to be “an oppressive academic voice telling people how to think” and instead wanted it to be “casual, but informed and diverse”. After becoming a surprisingly successful blog, which developed into taking contributions from a whole host of architects, researchers, and writers, Cairobserver was distributed in print for several issues. Cairobserver, which reached a keen and engaged audience on the back of the hype around blogging, however, has reinvented itself to exist mostly as an Instagram page of beautiful, interesting, and, at times, unusual images of Arab design, architecture, and visual culture interspersed with Mohamed’s observations and thoughts.

Another notable project that saw exhibitions in Cairo and London, was when Mohamed Elshahed collaborated with the British Museum for a project entitled the Modern Egypt Project. Hoping to challenge orientalist and reductionist ideas about Egypt, which often entrap Egypt into only existing in a narrative of ancient Egypt or the Islamic period, the Modern Egypt Project instead displayed examples of modern Egyptian design to introduce a new narrative to people’s understanding of the country.

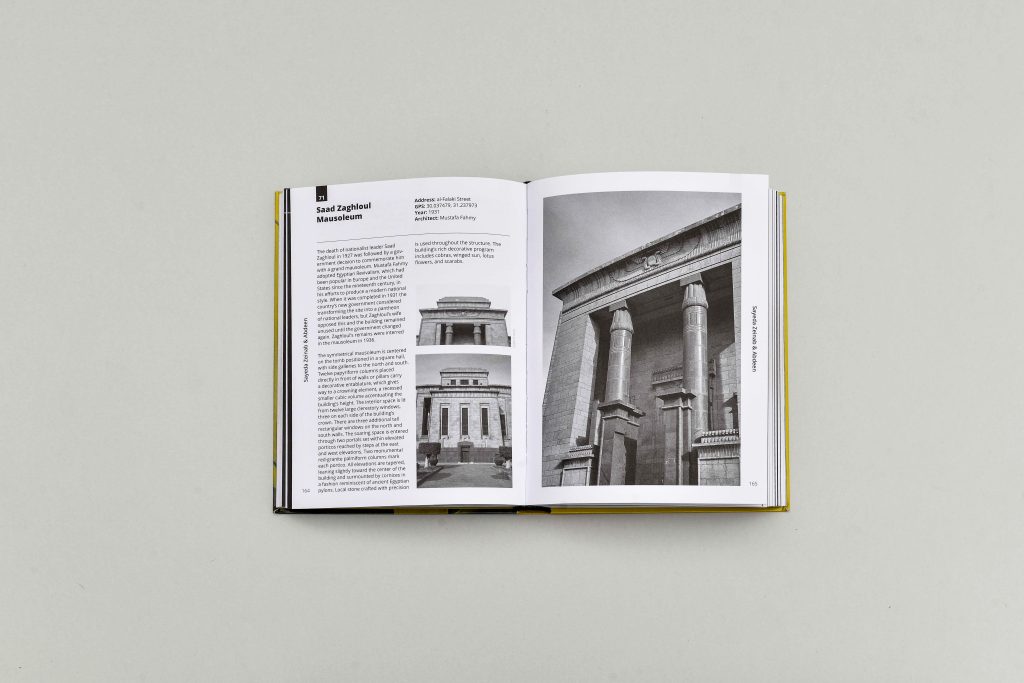

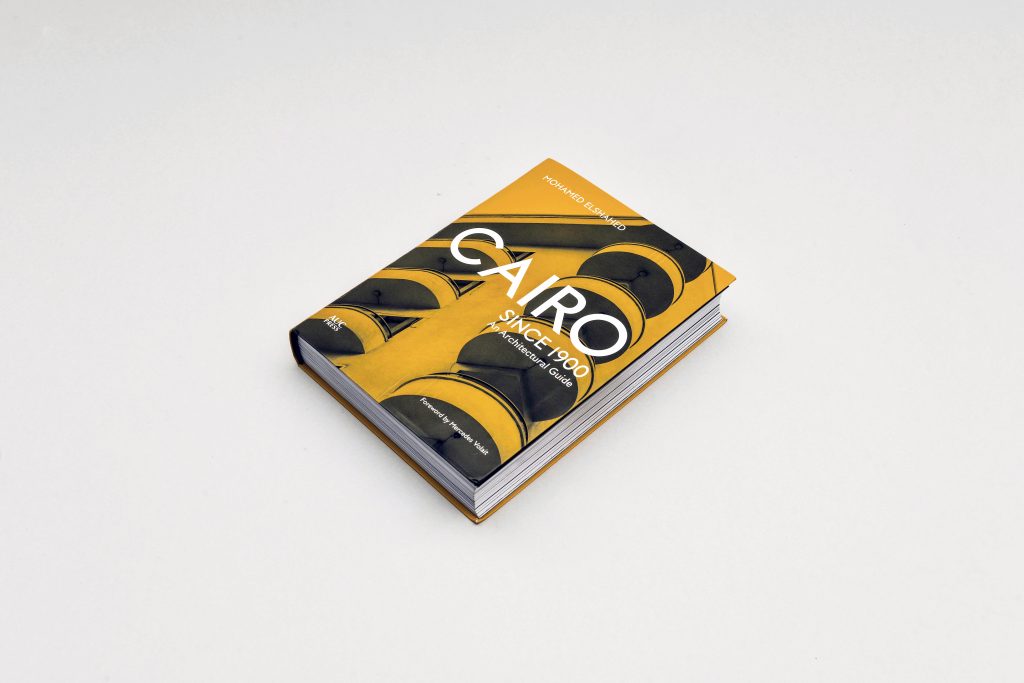

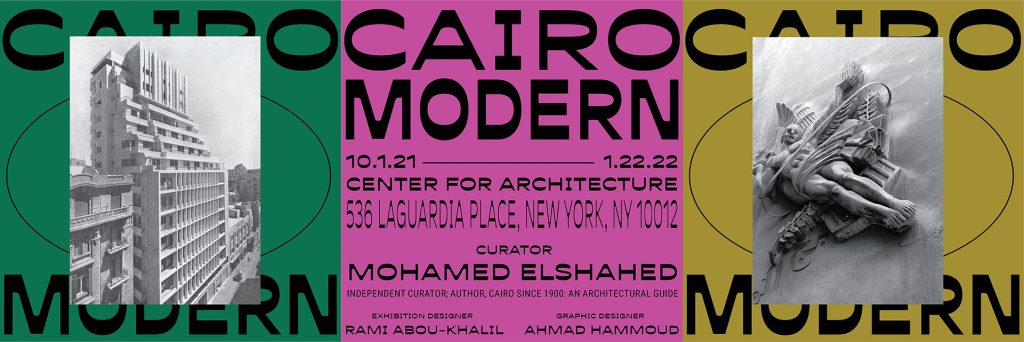

More recently, the American University of Cairo Press published a book by Mohamed Elshahed entitled Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, which was recently turned into an exhibition at New York’s Center for Architecture under the name Cairo Modern. The book and exhibition catalogue modern Cairene architecture in a bid to establish these buildings as an important element of the city’s urban fabric and architectural history.

Mohamed Elshahed has been a unique voice on modern Egypt and has seemingly been driven more by political, rather than strictly academic concerns. Seeing the academic discourse on the Arab world and that of art history and architecture being primarily driven from a Western viewpoint, Mohamed in many ways has worked against academic disciplines as opposed to within them. I sat down with Mohamed Elshahed to discuss some of his underlying interests behind his work, namely, what makes Cairo such a fascinating and important case study, the politics of the built environment, and whether colonial influence ever truly ended in Egypt.

Why Modern Cairo?

The fabled fourteenth century explorer Ibn Battuta glowingly described Cairo as the “mother of cities and seat of Pharaoh the tyrant, mistress of broad regions and fruitful lands, boundless in multitude of buildings, peerless in beauty and splendour”. Modern Cairo, with its enormous size, traffic density, and cacophony of sounds, however, often meets a different response and has been unusually absent, at least prior to the Arab Spring, from academic discourses. I pressed Mohamed on what he personally finds so fascinating about the city and what makes it a unique place to research and understand contemporary cities.

Mohamed described his fascination with Cairo as a place that has undergone “massive transformations that are the result of urban migration, shifting heritage, and changing political systems three times within a century.” He pondered, “imagine London going through that in a century, I mean it wouldn’t survive actually”, pointing towards the “magnitude of the things that Cairo has experienced in the past years”.

Another aspect that seemed to equally catch Mohamed’s curiosity and frustration was the lack of writing and academic focus on modern Cairo despite the immense changes it has gone through, which beg for further inquiry. Lamenting that “there is so much that has gone undocumented” and the lack of a proper museum of architecture, however, Mohamed found himself “attracted to Cairo from that lack of information, the haphazard documentation, and the immense forces and pressures and changes that not all cities would be able to handle.”

Did Colonialism Actually End?

“One of the interesting things to think about is that the post-colonial, as far as I’m concerned, never happened.”, Mohamed told me. He carried on to state that “look at what happened to Africa after the post-colonial moment. What happened is that everything continued, but even worse”. As an example, he went on to describe how “Cobalt is being extracted in Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world after how many decades of so-called independence and post-colonialism. It is basically just a mine for Western industries; before it was rubber that fuelled World War one, now it’s cobalt to fuel Teslas. So, colonialism has not ended, it just transforms, renames, and reshapes.” Relating it back to Egypt, Mohamed described how “we’re still marching on with the narrative of 1952 independence, but we don’t talk about what happened there and later neoconservative policies, which essentially for me are just a reformation of colonialism”.

At the root of a perceived inability to recognise continuing exploitative and coercive relations between nations in the Global South and Global North, Mohamed described how “aesthetics are not how we define colonialism, you have to look at what’s actually happening on the ground”. Expanding on this, Mohamed went on say how “I think of my parents in the 50s and 60s, as there was a kind of particular political and cultural milieu. The people really thought that they are now post-British occupation, for example, and other countries post-French occupation, and post whatever other occupation. When you’re in the moment, you don’t know everything, but with time, we know more. So, this is why the personal and political, the small picture and the big picture, are always connected”

Does Writing on Egypt and the Arab World Still Have a Eurocentric Bias?

“I mean, the Eurocentric frame of reference has not gone anywhere, it has been with us for 500 years and we just need to stop”, Mohamed stated plainly. As an example he had recently encountered in his life that was illustrative of the pervasiveness of Eurocentrism in understandings of the formerly colonised world, he described how for his ongoing exhibition in New York, “I’m talking about early 20th century Egypt and Cairo specifically, and for New York audiences, and even for someone who’s working at the institution that’s hosting the exhibition, I had to explain why colonialism is a relevant concept. I had to vocalize it, and actually say “well, you know, my parents were actually born in a city where soldiers from other places were walking down the street and there were curfews. My parents, and therefore, my life, is actually shaped directly by this”.

Mohamed explained this apparent refusal to acknowledge a colonial context by suggesting, “all of this is only possible with the continuation and the constant rebranding of a Eurocentric worldview that has not left us”. Before posing the proposition that “one of the ways to counter this is to think of how Eurocentrism has come about, and what it is really about. Because I think to really resist something, you need to figure out its dynamics.” Unpacking the ways in which Eurocentrism works, he proposed the innate connections between Eurocentrism with both colonialism and white supremacy, and how “this combination together minimizes, dismisses, belittles everything that’s not fitting within its frame of reference. Therefore, things become devalued, erased, and replaced by what is acceptable within a frame of reference that people are born into and think is their only reality.”

In relation to his own work with Cairobserver that has challenged commonplace notions of the city and his recent exhibitions with a specific focus on modern Egypt, insisting on the country being viewed through its contemporary existence, which “block out the noise as much as possible and look at what’s on the ground”, Mohamed offered a suggestion of how counter the logic of Eurocentrism. “It goes, I think, counter to the mechanisms of Eurocentrism to actually give value to the things that have been devalued, to fill in informational gaps on things that have been hidden or dismissed as unimportant, to speak about the place on its own terms, whatever place it is. Whether we’re talking about Bangladesh or Egypt, let it speak for itself by actually looking at what people say, what people build, and I think that’s one way to respond to the ever presence of Eurocentrism, because it really has an incredible power to redesign itself, rebrand itself, and there’s an incredible machinery around it”, Mohamed elaborated.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t Miss… Do We Need A New Name For The ‘Middle East’?