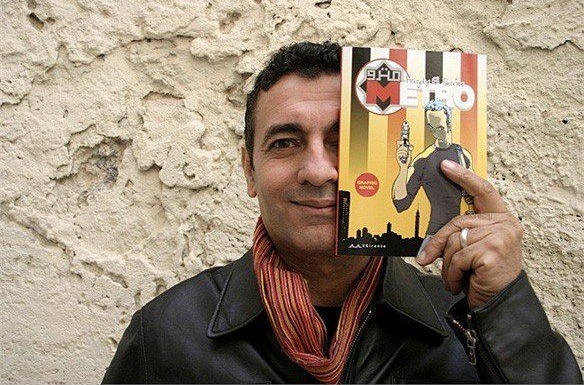

Magdy El Shafee is the pioneer of the Arabic adult graphic novel in Egypt. Many even refer to him as the godfather of this genre in the country. His book Metro was first published in 2008 by Malameh publishing house.

Soon after it was published, the police raided the publishing house and confiscated all copies of the book, and it was banned from further printing. The crime was “infringing public decency” and ultimately each were fined 5,000 LE.

El Shafee explained that Metro‘s court case is finalized and the judgment will not be reversed. So unfortunately it will remain officially illegal to be published in Egypt. The Arabic version can be ordered online through http://www.cspublishers.com/blog/ and it’s available in English at Diwan Bookstores & Kotob Khan in Cairo. He told me that he isn’t enraged by this fact, that he has come to terms with it and he says what’s done is done, no use in rehashing. It’s a fait accomplit.

Interestingly, Metro did really well in its Italian translation. It was even on the best sellers list for a very long time because the translator, according to El Shafee, contributed a lot to the work, especially because he was able to grasp the cultural subtleties and nuances of the original language. The Italian translation is written in Italian informal slang, a rough equivalent of the novel’s original Egyptian colloquial.

El Shafee told me that reading graphic novels, like V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd and Sandman by Neil Gaiman, changed his life. “These books, they made my head spin,” he said. He is also very pleased that publisher Dar-Al-Tanweer has released the award winning Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi and Palestine by Joe Sacco in Arabic.

“This is the type of work that inspires me. I knew how to draw and how to create fiction, so this is what I wanted to do. I wanted to create art that changed people, changed their mindset, that makes your head twirl like mine did when I read these novels.” He is currently working on several projects, but has put them aside. When he feels they are ready, they will then be published, he said. “Art is hope.”

Last April, when El Shafee was participating in a protest, he was arrested along with about twenty others. The #freemagdy Twitter campaign that ensued is the reason why he was released, he says. He spent a total of four days in prison, two in Tora and two being moved around.

When I asked him about how he was treated in prison, he didn’t elaborate but he did tell me that they were grouped together like sardines and hit with the backs of rifles. This was not his first brush with the police and he says the officers had differing attitudes. They were inquisitive and it seemed like they were trying to understand him, and maybe second-guessing their orders. He even mentioned how one of them told him, “I’m gonna put down my pen [off the record] and explain to me why?”

El Shafee underlines how the ideals of the revolution are simple freedom, dignity, bread and social justice. These cannot be more true or more significant when one is in the creative/artistic realm. In order to produce a new song, a new book, a new piece of art, one needs freedom – not just to be able to do what you want – but also economic freedom to produce, market, and sell your art.

Egypt not only has censors that delay and put hurdles in the process, there are also so many barriers to entry and red tape that unless you have extreme conviction and belief in what you do, like El Shafee, it’s an uphill battle to break through and persevere with your art.

When I asked him about the future of Egypt, he says it sometimes seems dark when figures like Mostafa Bakry are on the political stage. He explains how having such loud men at the forefront makes him cringe and feel like the past two years and the deaths from this time period were all in vain.

These “figures are dangerous, they promote the wrong societal values,” he said. Yet he explains that when he was taken by the police last April, the whole truck was filled with activists who were all under twenty – that means they were maybe sixteen when the revolution happened. “They give me hope,” he said. “They are the future.”

The people around him are also what give him hope, like Mohamed Hashem of Merit Press, the activists and the human rights lawyers. “The people who stood by me and surrounded me on a day to day basis. This link and network of people are a once in a lifetime possibility, you can’t ever force this type of cohesion to happen. When it happens you can’t imagine what life was like without these people. It can’t be found anywhere else in the world. Together we created a bond and that’s what keeps me positive and moving forward.”

When I asked him about the rise of and interest in graphic novels, like Autostrad from Division Publishing, which he was a part of, and Tok Tok, which is now on its 9th issue, he praised these initiatives. Yet he believes graphic novels are pop art and should be accessible and affordable to the common man.

He further explains how the problems in this field in Egypt are twofold: There is lack of good scenarists and the publishers are very weak. “We are in dire need of scenarists who understand the genre well, and who are free and liberal enough to approach any work with professionalism and zero reproach.”

How about publishing outside of Egypt? Although Lebanon is great in availability of both publishers and scenarists, “I want to make comics that are accessible to the common man, and producing abroad will make it costly, and hence only be appealing to an elitist class. And that’s not what I want. Comics are simple and should be easily accessed.” But there is hope, with emerging publishers like the Comic Shop and the 9th Art in the country.

The mood in Egypt now is dynamic. According to El Shafee, there are lots of workshops happening and this is good for the genre, but not enough production.

“I am not belittling the importance of workshops, but there must be something that comes out of this process too. I just turned down a workshop for this very same reason. There were funds for a workshop but no funds to produce a piece of art resulting from the workshop. Simply, there must be more output. There is a lot of discussion, and this is good, but alongside it, more work must be produced. It can’t be all talk and no action.”

When I asked if he’s thinking of turning Metro into a movie like Persepolis, he said he believes that this type of endeavor satisfies the ego of the artist more than the art itself. He believes that it should be kept in its own genre, because that keeps it genuine. Although putting it on film might give him more exposure, economic prosperity and success, he still feels that that would not be staying true to the genre, and that is what is what is most important to him.