Today is the last day of Banned Books Week, a celebration of outlawed reads that started in 1982 to counter the practice of schools, libraries and universities banning books across the USA. Amnesty International turned it into a global movement, highlighting countries where authors were persecuted or jailed for their books. Unfortunately and unsurprisingly, Egypt is on this list. For example, the graphic novel Metro by Magdy ElShafee was banned for offending public morals.

Countries, governments and institutions that ban books should realize that their banning only leads to increasing their popularity. The reasons given range from blasphemous, ungodly, encouraging sexual promiscuity, profanity, satanism, undermining religious ideals, psychologically damaging to a whole variety of inappropriateness.

But the root of banning? Fear.

“It’s fear that makes us lose our conscience. It’s also what transforms us into cowards”.

This quote is by Marjane Satrapi, who wrote the award winning and banned Persepolis in 2007. The French animated film is based on her autobiographical graphic novel of the same name.

Banning has been going on for hundreds of years. Today’s classics were banned in their time, from To Kill A Mockingbird and The Scarlet Letter to Fahrenheit 451 and 1984. The list is so long, it seems there isn’t a successful author that hasn’t been on this list at some point or another. There are even countries that ban the Bible and/or the Qur’aan.

Let people read what they want. Especially in this day and age, books are so accessible across borders. All those who ban should find something better to do with their time.

In honor of Banned Books Week, I chose to write this week’s review about Flaubert in Egypt, which is a compilation of Gustave Flaubert’s travel notes and letters of his voyage to Egypt in 1849. These were translated, compiled and published by Francis Steegmuller in 1979. This is not a book for the skirmish, and would definitely annoy every censor in Egypt. So it felt appropriate as a choice for several reasons.

First, because Flaubert’s Madame Bovary was banned in France in 1856 for going against public morals. His voyage to Egypt inspired Mme. Bovary and he was transformed as a writer into a realist. Second, because the book tells us as much about 1849 Egypt as it does about Flaubert. Third, Shereen ElFekki’s Sex and the Citadel says that

“Flaubert proceeded to fuck his way up the Nile.”

This should ignite anyone’s curiosity to read it.

This should ignite anyone’s curiosity to read it.

Flaubert in Egypt is both travel literature and erotica, leaning more on the erotica side. With this year’s best-selling Fifty Shades trilogy, which caused worldwide upheaval, it seems racy passionate letters never seem to fall out of fashion.

As an Egyptian, I couldn’t help but be offended by Flaubert’s colonialist perspective of Egypt and automatic assumption that the native culture is uncivilized – from his constant reference to Egyptians as “negroes” to his arrogant view that he could convince France to conquer Egypt and that it could be easily done in a week.

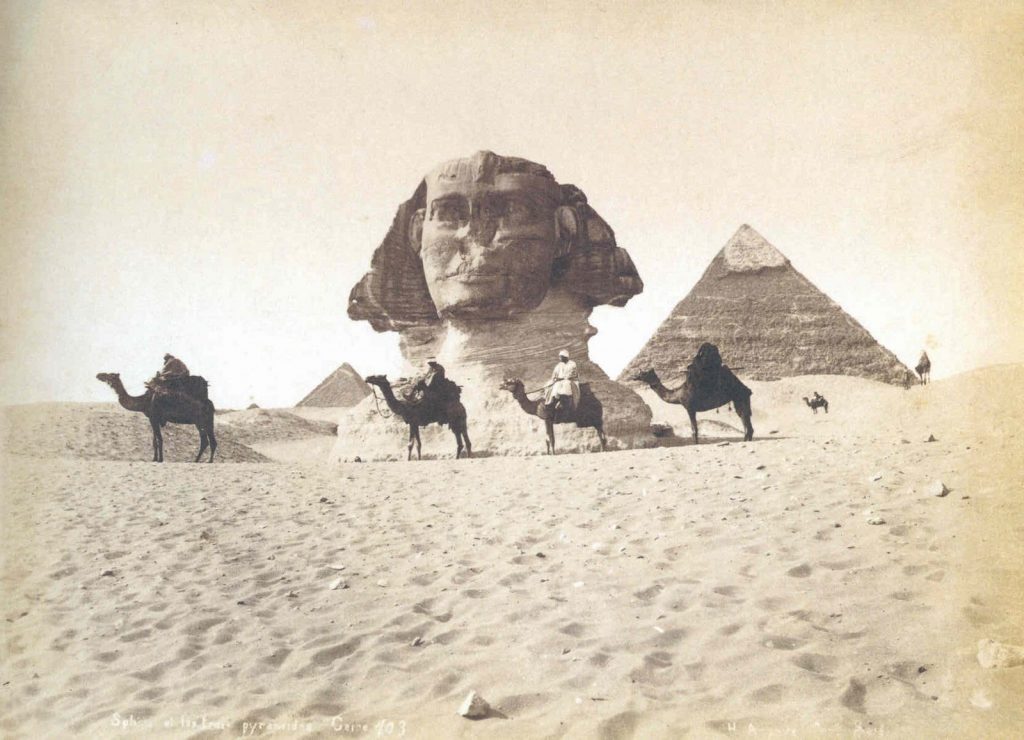

Flaubert and his travel companion Maxime Du Camp were both 27 years old at the time. This voyage led to the first ever publishing of photographs of Egypt by Du Camp, who many claim transformed Egypt into a real tourism destination.

They traveled by boat to Alexandria where they started their journey, then went by steamboat to Cairo and all the way down to Luxor and Aswan. This tour is still done now. Today’s experience would still be similar, with Egypt’s timeless beauty, the exquisite silence of the Nile and of course the monuments.

Spoiler alert: It’s not surprising that at the end of all these raunchy sexual adventures, Flaubert and Du Camp end up getting syphilis.

The fascination for me, however, comes from the constants between Flaubert’s 1849 and our 2013: the Khamaseen, the devotion of the Copts, the weather, the burning desert sun, the Pharaonic temples and monuments, the attitudes of Egyptians towards foreigners (khawaga), the European quarter Ezbekiya, which in modern day Cairo might lie in Maadi or Zamalek. Even in 1850, people were leaving Egypt in disgust because the country was falling into ruin at the hands of Abbas Pacha, the tyrant.

East for the British was India, but for the French it was Egypt. Although the British were in Egypt longer than the French, there always remained a special connection between France and Egypt. Edward Said in Orientalism (1979) analyzes Flaubert’s relationship with the courtesan Kuchuk Hanem and how it shows the imperialistic perspective of the French.

A complete opposite contrast to Flaubert is the nonfiction travel biography of Gertrude Bell by Janet Wallach (2010). As the first woman graduating from Oxford in History during the same decade that Flaubert was in Egypt, she was designated by the British Empire to map, divide and research the Middle East. Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell: Adventurer, Adviser to Kings, Ally of Lawrence of Arabia, gives a completely different perspective, albeit still colonialist, of what Egypt was like in the same time period.

Through all the ups and downs in our history, I leave you with my favorite quote from Flaubert in Egypt because it is one of the things that remains true:

“Egypt is a great place for contrasts: Splendid things gleam in the dust”.