No, this is not an article that is going to claim that Egyptian men should fight sexism and sexist culture because their wives, sisters, mothers, and friends are women. Neither, is it an article encouraging men to utilize their privilege to help women end sexism.

This article is about the ways in which sexism, in and of itself, negatively affects men. This is not to say that men do not have a lot to gain in sexist models of society. Rather, it is to say, that no one wins in a society structured around the patriarch, but most writings – including my own – tend to focus on the losses incurred by women.

Although I think this is a fair and necessary bias – considering the fact that women especially lose when society is sexist, and considering the need to correct the effects of sexist culture codes and laws – I think that it is important to seriously considers the pressures placed on men and boys by this model of society.

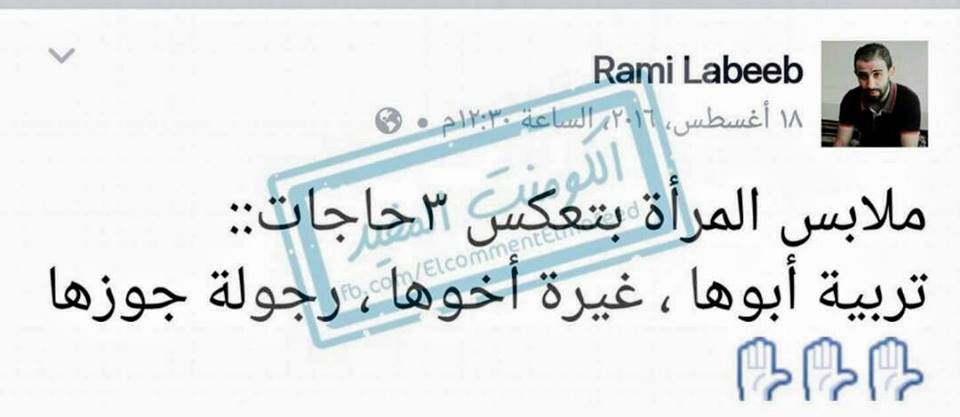

Consider the tweet above, for example, which translates into “A woman’s clothing reflect three things: Her dad’s ability to raise her well, her brother’s protectiveness, and her husband’s manhood.”

My initial reaction to this tweet was how the sexism inherent in Egyptian honor culture allows for a notion of womanhood that is inevitably tied to the control of a patriarch.

While this, in my opinion, is a fair criticism of honor and mainstream culture in Egypt, I also think that perhaps this culture places an unexplored pressure on men.

This point was made clear to me when one of my guy friends said: “If my wife were to walk down the street while wearing a really low-cut top, people will not only harass her, they will also bully me for allowing her to dress this way.”

He further added, “My manhood will genuinely be challenged by everyone around me, and by strangers.”

Firstly, the assumption that this man has an opinion on what his girlfriend is wearing is something that is taken for granted by the everyone in society.

Secondly, and consequently, because it is taken for granted a man faces genuine social sanctions should he choose not to act upon this patriarchal privilege.

While my response two years ago to this kind of comment would be one that logically assumes that this friend of mine has some serious insecurities because he cares so much what people think; I think that having this response now would be problematic, to say the least.

Do not get me wrong, I do not think that anyone’s sense of self should not be so easily challenged by what anyone has to say.

This is much easier said than done in a society that bullies men if they do not utilize what has socially come to be seen as a right of gender, not a privilege bestowed upon one’s gender due to sexism.

My friend’s case does not exist nor operate in a vacuum. Take, for example, the genuine concern the majority of men would have if their wives or partners were making more money than they were.

The concern comes from a model that has for years defined manhood exclusively by the ability to be the prime breadwinner in the household.

Consider, also, the idea that men are not allowed to cry. Indeed, anyone who has a young male sibling will have surely either have told or heard someone tell this young male not to cry because “el regala mabt3yasth” (men do not cry).

This is not to deny legitimate psychological research that reveals that there are differences of emotional expression to be found along the lines of gender difference.

Rather, it is to say that denying someone an opportunity at emotional expression under the claim that it is feminine, and hence inherently weak, does reflect another very real form of social pressure faced by men.

Admitting that some differences can be observed along the lines of gender is one thing, using this admission of difference to create a gendered hierarchy that denies certain emotional expressions while applauding some is a whole other thing.

To sum it all up, it seems that performances of masculinity in the context of Egypt’s honor culture, seem to be strongly ironically tied up with an assumption of crisis and fragility within that very masculinity; if you do not do this, you are no longer a man.