Last Jan. 25 (coincidentally, a key day for Egypt’s revolutionaries), Yemen’s National Dialogue Conference (NDC) wound up after more than nearly a year of on-off discussions. The talks – six hours a day, five days a week in normal situations – started last March and were a key part of the murky 2011 agreement brokered by the UN and the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) that saw long-time President Ali Abdullah Saleh step down after 33 years in power at the peak of a momentous uprising that many feared could have spread to other Gulf territories. Let’s not forget that Yemen flanks major shipping lanes vital for both the West and Gulf countries.

Many have hailed Yemen’s NDC as a model for other Arab countries where uprisings have been taking place since 2011 onwards, particularly because of its inclusiveness and constructiveness. In fact, Tunisia’s success was also the outcome of a National Dialogue characterised by consensus. (This has not, however, been the case in Bahrain and Libya, where, in spite of the outrageous silence of the media, the situation is worsening by the day.)

The NDC agreed on a document on which the new constitution will be based. Mr. Hadi, the former vice president from the old guard that relieved Saleh in what some still call a very murky transition process, will remain in office until the new constitution is approved and general elections held. That is, of course, if the government is able to tackle the many logistical and security matters that for now render it impossible for the elections to take place in 2015.

The 565 Yemenis that composed the NDC were drawn from an array of different movements and ideologies. The preparatory committee already ensured the presence of members of the former regime, other national forces and revolutionary youth entities. On paper, each delegate was equal – the votes of youth activists and feminists counting as much as those of ministers and Islamists. Backers of the Houthi rebels, who have been fighting against the rulers in Sana’a for years, mingled freely with members of the government.

The NDC was composed of all major political and societal forces, including the party of Saleh, the GPC (112 seats) and opposition parties, most importantly the Islah Party (50), the Yemeni Socialist Party (37), and the Nasserist Party (30). Quite remarkably, the NDC also comprises representatives of the secessionist movement in the South (Hirak, 85 seats) and the Houthis in the North (35), in addition to representatives from youth (40), women (40), and civil society organizations (40). However, many still complain about the unrealistic nature of the group.

As a delegate put it to The Economist: “there are two Yemens, the Yemen inside the conference and the Yemen outside it”. After years of crackdowns, this affirmation is not hard to believe if we take into account the non-existence of independent institutions or a unified opposition. Delegates were divided into nine working groups, ranging from security to development.

The agreement constitutes an important formative step in the field of building a civil state. It successfully defines the identity of the state (Yemen as an Arab Muslim state), its form and system of rule. Recommendations also refer to the need to promote justice for abuses during the 2011 uprising, defend women’s equality and promote other basic rights. Even though this is not set in stone, the final report also recommends using Sharia as the primary source of legislation

The real hot potato: A future with two countries?

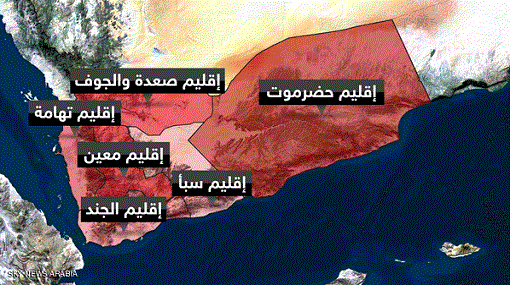

Despite its achievements, the NDC ended with a bitter note: Its participants could not reach an agreement concerning an eventual partition of the country. Or should I say re-partition, as the country was already divided into South and North Yemen between 1918 and 1990. A partial solution was brokered, but only by extending the transition process. It is believed that the constitution will create a number of regions that will enjoy semi-autonomy, but this will surely not be enough for certain southern separatist movements that have spread chaos and fear.

Sectarian battles have also been taking place in the northern part of the country, where Houthi rebels (of the Ansar Allah movement, which is a religious/political armed movement that belongs to the same doctrine espoused by Iran) have gained control in many towns. The Houthis are in conflict with their fellow Shiites, a conflict that has left behind the death of many of their compatriots, as well as the displacement of others. The other camp is represented by the Salafists who belong to a Sunni religious group espousing Wahhabism, the official Saudi Arabia doctrine.

While Southern secessionists want to divide Yemen into two regions with the south having significant control over its own affairs, a number of northern parties favour a six-region federation. In other words, everybody agrees on the need for Yemen to be a federal state, but the main dispute seems to be about the number of regions. Not coincidentally, the south (particularly the Hadramawt region) is the area where the bulk of oil may be found; the country relies on crude exports to finance up to 70 percent of its budget.

However, there is reason to believe that the debate should not hinge on whether there is one unified southern identity versus a northern one or not. And this is because most cities and towns are deeply tribal. In fact, tribes were one the most prominent forces that responded to the revolution supporting the youths, as well as the change it brought about. Another contentious issue is the division of legislative and executive powers between the south and the north, especially since the north has 75% of Yemen’s population, although southern lands are wealthier and more than twice the size of northern lands.

The source of tension and hurt in the south goes, however, well beyond administrative concerns. Even though political parties and leaders reached a badly needed agreement in 1994 about the south, violence broke out between North Yemen and the former Marxist South a few months later. Then President Ali Abdullah Saleh crushed southern secessionist forces and preserved the union.

After Sanaa’s victory in the 1994 civil war, swathes of southern territories were sequestered by powerful elites from the capital, while thousands of locals were removed from their houses and jobs. Southerners still complain of blatant discrimination – namely their inability to get state jobs – seizure of state assets by northern authorities and withholding of state pensions from families of soldiers killed in the conflict. As it is the case in many Arab countries, transitional justice was lacking then and is here now to settle accounts.

Pending issues

As it is still the case with the other winner of the Arab Spring, Tunisia, Yemen still has to face serious challenges. The economic situation is particularly worrying. Oil resources are tremblingly and quickly declining. Yemen is the Arab world’s second poorest country after Mauritania. The country has the second highest unemployment rate in the world, up to 50%, according to the Social and Economic Development Research Center. Youth unemployment is particularly acute, the prospects in this sense being especially dire as the country suffers from a “youth bulge”. Many families depend on remittances from Yemenis working in Saudi Arabia, one of the main reasons why the GCC had no qualms in intervening when needed.

Social problems include poverty, poor quality of life and lack of social services. Grave humanitarian shortfalls have also been reported – particularly related to the strong presence of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and the drone counter-attacks carried by the U.S. – and rampant insecurity is becoming the norm in nearly all areas. For instance, early before the announcement, gunmen killed a representative of one of the main rebel movements near the capital. Ultraconservative Salafists and Sunni tribesmen allied to them in several northern areas have been operating despite a government-brokered ceasefire.

An uncertain future

The NDC’s main goal was to seek out all possible avenues to save the country from total collapse. Even though a vital agreement has been reached, nothing really guarantees yet that the solution will prevent all parties from cascading back into strife. The new constitution will have to tackle not only practical issues but also transcendental questions such as transitional justice and national reconciliation. In fact, Saleh and the main figures of his regime won amnesty from legal and criminal prosecution and continue to dominate the political arena.

Meanwhile, the revolutionary youth have consistently returned to the streets of Sanaa, Taizz (in Yemen, the Freedom Square takes this name) and Aden, demanding the exclusion of Saleh and his associates from the political scene. And there is where the main difference between the Yemeni Spring and the others lies: While in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, the ousting of the tyrant and its ancient regime turned into the main goal of both revolutionaries and the population, in Yemen, the chief widespread objective is stability, regardless of the honourable dreams of brats like Yemen’s joint 2011 Nobel Peace Price winner Tawakkol Karman and the likes.

“Sanaa or bust, no matter how long the trip” is an expression usually repeated by Yemenis in reaction to the daily difficulties they face. No wonder why.

WE SAID THIS: Catch up on Tunisia’s political situation here.