Tucked away in the labyrinthine streets of Al-Ataba Square, amidst the cacophony of street vendors, car horns, and hurried footsteps, lies a rare sanctuary of precision and patience: the Francis Papazian watch shop. From the outside, it might appear as any other small business in downtown Cairo, yet stepping under the arcade reveals a different world. Wooden counters, yellowed advertisements, and drawers brimming with parts from decades past give the space the quiet dignity of a living museum. There, time is not just measured, but honored. At first glance, it’s clear this place is over a century old.

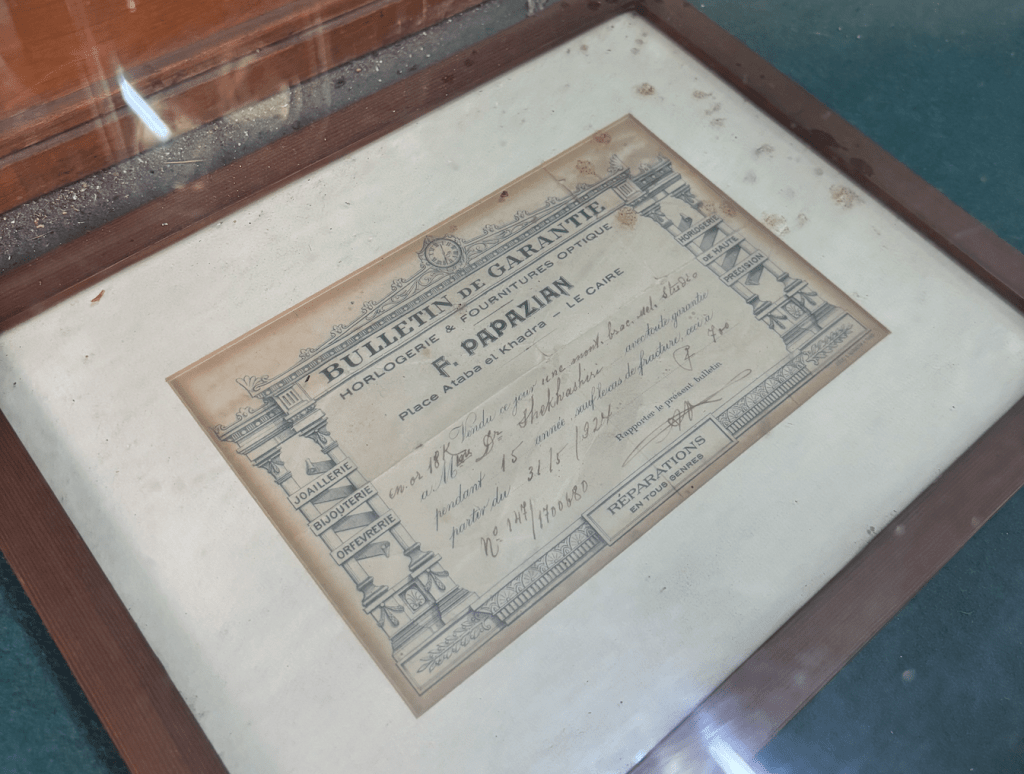

The story begins with Nerses “Francis” Papazian, an Armenian craftsman who arrived in Egypt in 1903 to establish the shop.

“My grandfather, Sir Francis, founded the shop in 1903. He unfortunately passed away early, in the forties, so my father, who was eighteen at the time, had to take over with his siblings,” Ashod Papazian explains. That early moment set the tone for a family dynasty dedicated to precision, skill, and devotion. Even as Cairo evolved and the neighborhood transformed, the Papazian family maintained a steadfast presence. The shop became not only a hub of craftsmanship but also a repository of stories, lives, and generations passing through downtown Cairo.

It’s in these details—the way Ashod describes polishing a cracked dial from his grandfather’s era or the smell of sunlit wood and metal—that the shop becomes more than a business. It becomes a mirror of Cairo’s heartbeat, capturing the rhythm of a city where modernity constantly collides with memory.

The Papazian Diaspora

The Papazian family’s reach extended far beyond Cairo. Ashod recounts that his uncles moved abroad—one to America and another to Canada—leaving the profession in their hands. “The one in Canada celebrated his 100th birthday. I asked him, ‘Waiting for what?’ He said, ‘Waiting for the relief.’

He’s in a good place, his mind’s working well, but of course he left the profession long ago.” Another uncle trained in Switzerland, spending four years mastering the craft in Le Locle, a town famous for horology, before eventually moving to Germany.

Papazian reflects on the nature of the craft itself: “This profession is like a hobby. You don’t need to work for someone else; you can practice it anywhere in the world. But you must be a professional watchmaker, because this is a sensitive art form. You’re not a mechanic, you’re not a cobbler—you deal with delicate, precise pieces. It’s difficult work, and you have to love it deeply.” His words underscore the essence of this craft: patience, devotion, and a rare combination of technical skill and artistic sensibility.

This devotion explains why the profession is dwindling worldwide. “Globally, watchmaking is dying,” he says. “Here in the area, there were more than 25 professional watchmakers. Those who passed away, emigrated, or went to Australia or America kept practicing the craft abroad.”

In Cairo, too, much of this knowledge was tied to immigrant communities, particularly Jewish and German-Jewish artisans who once ran shops in downtown. Many left after political upheavals, leaving a void that the Papazians were fortunate to survive.

The Heart of Al-Ataba and Its Patrons

The shop’s location in Al-Ataba Square is more than geographic—it is symbolic. The square has always been a melting pot of people, commerce, and cultures, a microcosm of Cairo itself. “

The shop didn’t just sell or repair watches—it became woven into the daily life and history of Cairo. Ashod recalls famous clients like actors Yusuf Wahbi, Amineh Rizk, and Ahmed Zaki, as well as officers such as Abdel Hakim Amer. “Ahmed Zaki would come with two bodyguards, and he would just call out to my father,” Ashod says with a smile. “Abdel Moneim Ibrahim, Fuad Al Mohandes… and many others came through here.”

This continuity extends to everyday patrons as well. Ashod tells of a young man who arrived recently with a watch that had been in his family for generations: “Overcome with emotions, he said his grandfather and father were customers here. It’s rare—most shops don’t have this continuity. We repair something, and it’s checked again and again over the years. People leave their watches here for decades.” Even simple anecdotes become profound windows into Cairo’s social fabric, revealing how craft, memory, and trust intersect.

The stories are often deeply personal. Ashod recounts an encounter with a man named Nour El-Sherif, who left a modest Swiss watch in the shop for years. “I joked about his name—like the actor—but he had left the watch for so long. Eight years later, he returned. He was a former army officer, and as soon as he said his name, I remembered everything because of the similarity. We had kept it safe all that time.”

Another client had dropped a gold watch in the 1950s, only to return thirty years later to have it repaired. Yet it’s curious that he had assumed the store would always be there—something that puzzles me personally.

Even Ashod himself seemed to take it for granted, until the customer replied, “I mean, where would you go?” If that response reflects anything, it’s Francis Papazian’s place as a staple in the heart of Cairo. The shop is part of the city, and the city is part of it—and over time, that relationship has become simply irreversible.

Craft, Culture, and the Future

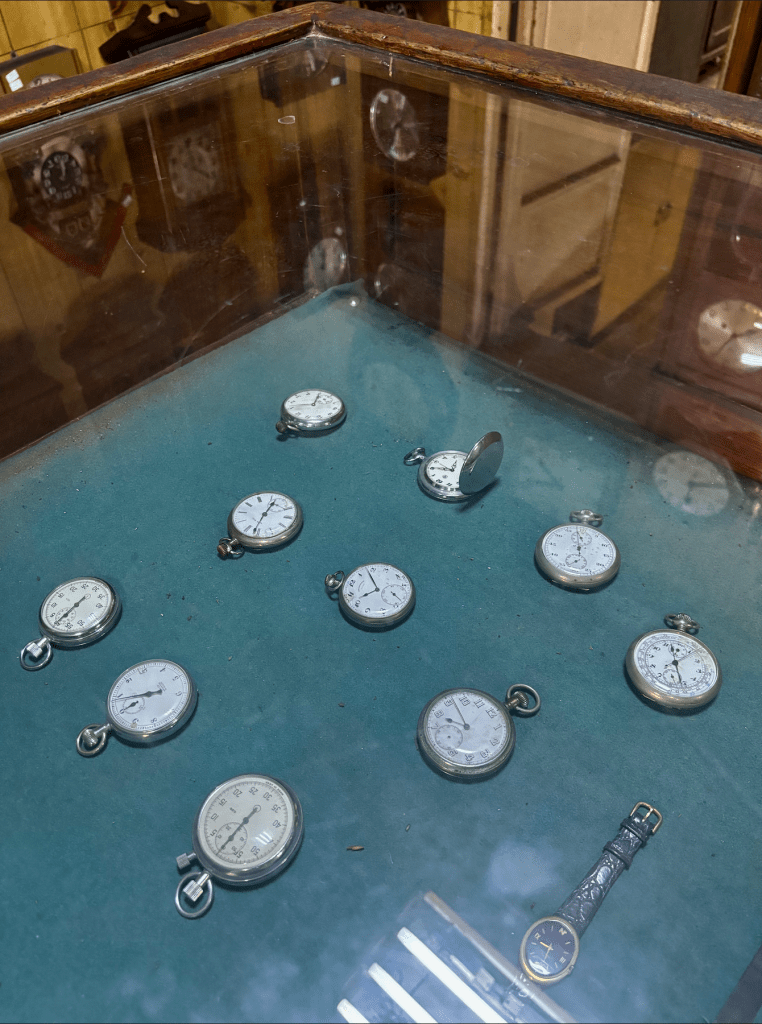

The Papazian workshop is also a living chronicle of horological history. Ashod proudly displays watches from the 1930s and 1940s—French-made pocket watches in pristine condition, some with intricate silverwork and mechanical marvels that are impossible to replace.

“When I see these, I have to buy them. They are irreplaceable. I love the old ones,” he says. The collection isn’t just for show; it is a tangible link to craftsmanship that predates mass production and disposable culture.

Ashod’s reflections also shed light on the evolving tastes in watchmaking. “In the 1950s and 60s, people were connoisseurs of Swiss brands—Jaeger-LeCoultre, Omega, Cartier, Longines, Movado. Each piece was meant to last a lifetime. Today, people buy many watches casually, sometimes Chinese or Japanese. Some Japanese brands like Seiko, Orient, or Citizen have improved remarkably, but they are hard to find.”

Beyond watches, the shop mirrors broader cultural shifts in Cairo. It embodies the cosmopolitan nature of a city that has hosted Armenians, Greeks, Europeans, and Egyptians, and it bears witness to migrations, revolutions, and societal transformations.

The Papazian shop remains a quiet monument to this layered history, resisting the pull of modernization and flashy commercial expansion. Ashod explains, “Even if future rent laws force us out, we could continue the craft at home.” Reflecting an incredible persistence to carry on the family’s heritage, Ashod Papazian protects the craft at any cost—defying time, place, and circumstance altogether.

This dedication has shaped how the Papazians work. Repairs are methodical and exacting, with attention to the tiniest gears and springs. Ashod emphasizes, “The profession requires thinking as if you’re composing a piece of music. It’s exhausting for the eyes and the mind. The old pieces from the 50s and 60s aren’t easy to reproduce. People often don’t understand this artistry, which is why the craft is dying globally.”

Francis Papazian & Cairo

What sets Francis Papazian apart is its persistence, its human stories, and the way it reflects Cairo itself. It is a shop where time literally and metaphorically stands still, where the past is carefully preserved while the city around it roars ahead. Each repair, each consultation, each treasured return of a watch embodies a dialogue between generations—between fathers and sons, between craftsmen and patrons, and between history and modernity.

Ashod’s personal reflections capture this spirit: “We started with my grandfather, continued with my father, and then my brother and I. It’s a profession that demands love, patience, and deep understanding. Sadly, the next generation—my children or the children of our apprentices—aren’t interested. That’s not just in Egypt; it’s worldwide. Yet for now, we carry it forward.”

In a bustling neighborhood like Al-Ataba, where streets are alive with vendors, buses, and the hum of Cairo’s ceaseless energy, the Papazian shop is an island of calm and continuity. It is a living archive of skill, culture, and memory. It is, in Ashod’s words, “not just a shop—it’s Cairo’s heartbeat, captured in gears, springs, and polished dials.”

WE ALSO SAID: Don’t Miss… Sip & Sign: Inside the Story of Lebanon’s First Sign Language Café