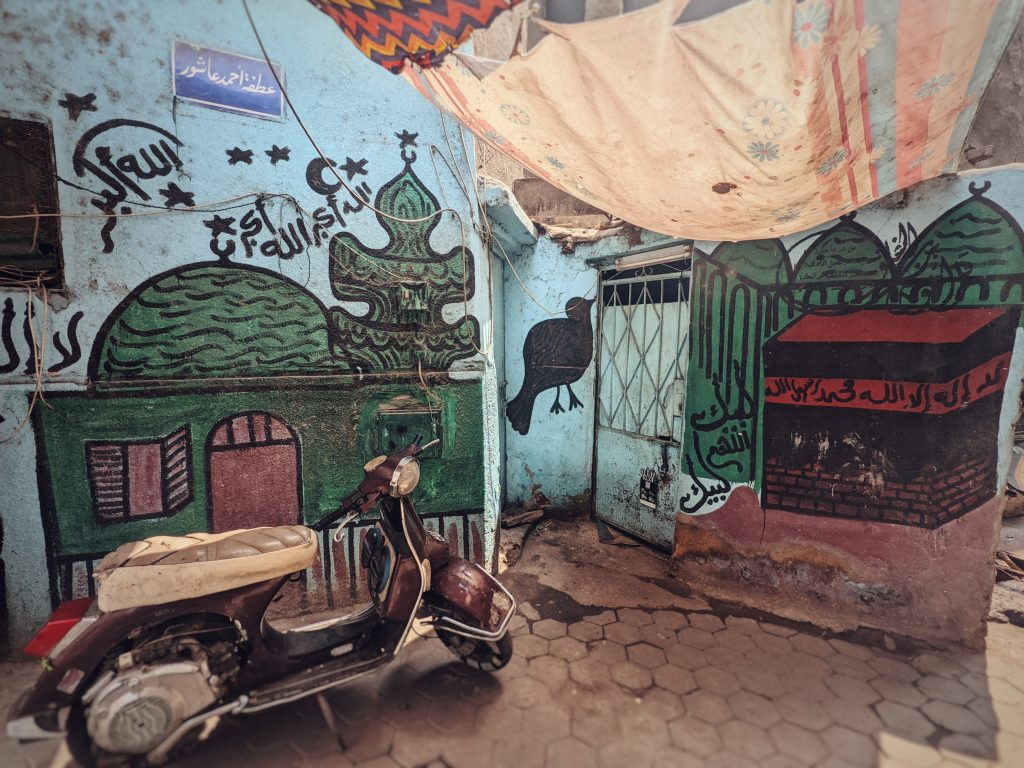

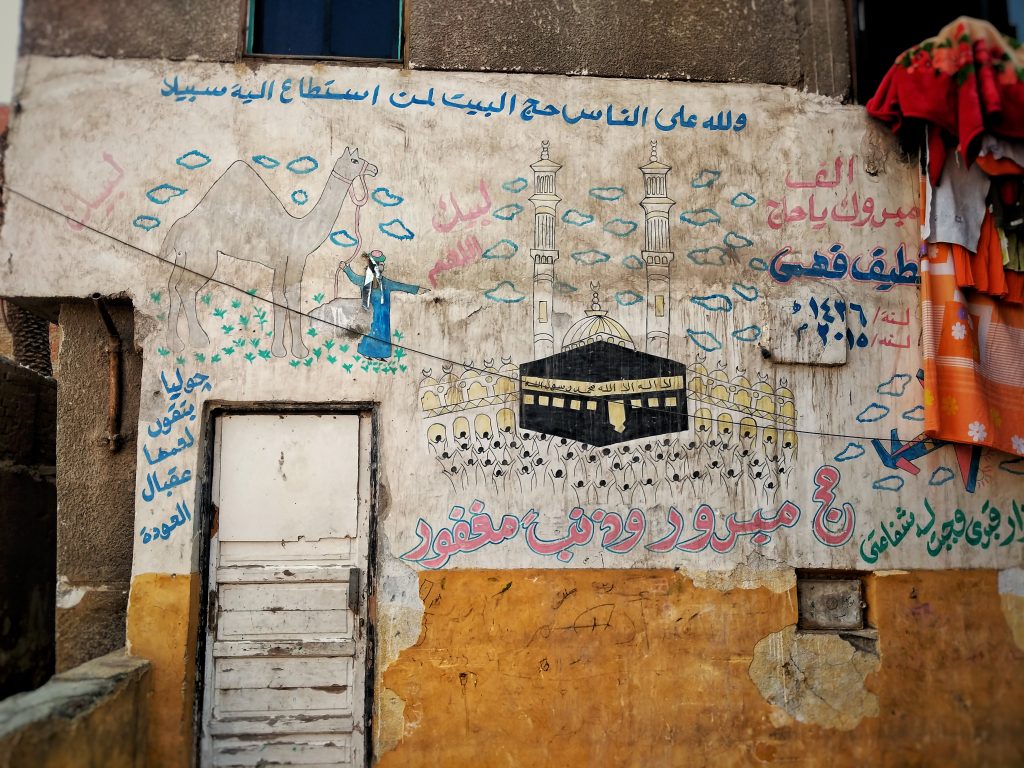

In Cairo’s al-Qarafa, known more commonly as the City of the Dead, I met Um Mohammed, an elderly and cheerful woman, sitting on a chair at the front of a house adorned with colourful depictions of the Ka’ba surrounded by worshippers next to images of planes, ships and palm trees. She enthusiastically explained that this joyful mosaic of Islamic motifs celebrated her pilgrimage to Mecca for Hajj ten years ago and was a gift from the neighbourhood to commemorate her completing this momentous part of her life.

Grinning with an unmistakable sense of pride, she told me that as one of the Five Pillars of Islam, completing the Hajj pilgrimage bestows upon him or her blessings, forgiveness of sins, a new-found respect, and is remembered by many, including Um Muhammed as one the most important moments in their life.

Hajj is an annual pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia, in which upwards of two million Muslims from around the world in a show of solidarity and submission to God conduct several rituals. After their journey to Mecca, pilgrims circle the Ka’ba seven times, walk between Safa Hill and Marwah Hill seven times, drink Zamzam water from the source, stand at Mount Arafat, throw stones at three pillars as a symbol of rejecting the devil, and spend a night at Muzdalifa.

The painted walls of the hajj murals in Egypt often detail important religious locations in Saudi Arabia, like the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and the Ka’ba in Mecca. Alongside these are often modes of transport to get to Mecca, be it an airplane, ship, bus, or even a camel in a nod to a long-gone past when the pilgrimage would take weeks, if not months. Images of crescent moons and other Islamic symbols also feature alongside Qur’anic verses and religious sayings. The most common Arabic inscription wishes the pilgrim ‘a pious hajj trip and forgiven sins’ and is often shown alongside the pilgrim’s name and the date of the journey.

Upon their return, the pilgrim’s blessing is brought back with them and is understood to be shared with the community around them. The newly returned pilgrim also secures the new title of hag or haga in the Cairene dialect for men and women, respectively, to inscribe on the communal record that they have completed Hajj, the last of the Five Pillars of Islam. The house too memorialises this new status of the hag or haga in the community, acting as a lasting reminder and announcement to anyone passing by their house.

These murals are normally a community affair, with the whole neighbourhood getting involved to decide on the design, colours and in the painting itself. When a professional painter is commissioned, it’s common for neighbours to pitch in some money towards the costs to welcome their fellow neighbours back from Hajj. Upon their return, the unveiling of the decorated house and the ensuring celebrations are mandatory, often going late into the night, jet lag be damned.

Hajj murals can also be found in Libya, Palestine, and Syria, but Egypt is considered to be the home of this artistic tradition. Although the artistic tradition of painting houses to welcome home pilgrims from Mecca is most prevalent in Upper Egypt, these beautifully adorned houses can also be found in rural communities across Egypt and in popular neighbourhoods in the major cities.

According to Yahya Nurgat, a historian of the Hajj in the Ottoman period, the tradition of hajj murals in Egypt was first written about by an Ottoman bureaucrat and intellectual by the name of Mustafa Ali, who wrote in 1599 that, ‘The nice custom is also highly praised by wise people that one of the relatives of the person that undertakes the pilgrimage, one who is known to be sincerely devoted to him, has the Quran verse on the pilgrimage [Āl ʿImrān, 3:97] inscribed with large letters on the wall of his door. Some even decorate it with various embellishments and colours. Those who pass through that street will know for sure that the owner of that house has gone on the pilgrimage that year’. Ali’s description is strikingly similar with modern-day practices and illustrates how deeply rooted hajj murals are in Egyptian culture.

The artistic tradition of painting hajj murals on the fronts of houses still endures as other Egyptian folk art practices dwindle in the face of the aesthetics of modernity and conservative interpretations of the faith that question such murals. While freshly painted murals can often be seen throughout Egypt, their styles and motifs have changed and transformed over the decades, often detailing the social history of Egypt as it debates its own identity. Hajj murals before the 1970s are said to have often featured images of the prophets Ibrahim and Ismail in addition to angels, until pressure from Salafists and other religious conservatives led to their replacement with motifs and images without religious figures more in tune with changing attitudes. Hajj murals of the past often also prominently featured pharaonic imagery and scenes of local life, as the focus on the Hajj existed alongside a celebration of one’s local identity and local community; however, this too is becoming increasingly rare due to an unease of mixing the sacred with the everyday.

Hajj murals are beautiful, colourful, and most importantly, meaningful example of Egyptian folk art. They constitute an artistic tradition that resonates joy and pride in the communities that practice it, and rightfully deserve to be celebrated and even preserved as a particularly Egyptian form of Islamic art and popular culture.

WE SAID THIS… Adverts For The Past: Cairo’s Retro Hand-Painted Billboards