Whether or not an Eastern woman feels ‘feminine’ in her own space, is a process that goes back

to societal roots and expectations that have “placed [them] in a tiny box that they can’t even fit

in,” as Egyptian visual artist Najla Said, so accurately explains.

It all started with her initial work with Unty, a streetwear brand inspired by Egyptian culture,

where one of her pieces depicted a woman wearing a t-shirt saying “bera7etha,” an expressive

word that, to the artist, was never intended to push forward a message or to be loud. If anything,

to her, saying that felt natural, and almost instinctive. Said was met with backlash and verbal

harassment from people in the streets during the shoot. She realized that this idea, that a woman

is self-governed in her own space, is a right that is not normalized in our society as it should be.

After receiving sarcastic comments such as “ah bera7etha tub3an,” and “bera7etha 3alashan

masla7etha,” Said says that in that moment, she “felt super visible and uncomfortable,” relating

to the mannequins in the surrounding stores, saying that it felt like a comparable portrayal of

women. Both “simply exist to serve a purpose tailored for others and not themselves.”

And this is exactly where the source of the problem lies. This precise inability of Egyptian women to move freely, has confined them in spaces governed and limited by the needs and expectations of their partners, brothers, or fathers, or just basic society.

After a separate series called “Yasmina,” inspired by classical belly dancing, the piece received

similar hostile reactions beyond imagination, due to the appearance of body hair on the model.

Najla says “it was so crazy that people when they see this picture, they’re so repulsed that they

feel like they have the right to rebel against it.” This suggests that every way a woman represents

herself is personal, and of relevance to them, that every single detail, even the visibility of her

body hair, or lack of it, is open for judgement or scrutiny. Moments and reactions like these are what have channeled the artist’s frustration into the inspiration for her latest series “Sister, Oh Sister.” The pieces explore the confined box to which Egyptian women are limited to, the idea of femininity, urging us to pose and shed light on certain questions: “What does it really mean to be feminine?” “Is there one way to be feminine, or can we move forward towards accepting that our idea of femininity need not align with someone else’s?” And more importantly, “How can our awareness of societal and patriarchal limitations help us to identify with our own femininity through our own terms?”

In one of the pictures of her series “And They Crashed The Party,” featuring a belly dancer, Said

explains that her inspiration came when taking belly dancing classes. She describes her

experience, that while observing the dancing, she realized that every single move and gesture a

belly dancer made is customized for her audience. The artist clarifies that she wasn’t categorizing

this as “good or bad,” but she wanted to offer a different portrayal of what belly dancing could

be, a way to embody the dancer’s own ideals rather than her audience’s. Najla was focused on

highlighting the notion that, through her dancing, she carries the power to express the idea that

“this is my body and I should have the capacity to do whatever I want with it.”

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Said’s series was in her picture ‘Never Too Many,’ inspired by

popular culture in Cairo. To the blind eye, all one can see is a picture of four women sitting on a

motorcycle, but to Najla, it carried a different meaning, that by placing these women in a

nonconventional context, she was reclaiming and widening the constraints of their space. From

one aspect, she was trying to highlight that each one of the ladies had an individual identity, yet

as a whole, they seem to harmonize together. Riding that bike, Said explains, was symbolic of

these women “heading somewhere together,” a place of freedom, a place of existence for no one

other than themselves.

This narrowed illustration of femininity is not only seen in the rigid attachment to conventional

expectations, but also in the paradoxical admiration of the non-conventional ones that

accompanies it, of multiple double standards that exist within our culture. It’s ironic, perhaps

amusing, that on one level, we as women are expected to follow the traditional “look,” but on a

whole other level, society is amazed and intrigued by Eurocentric ideals.

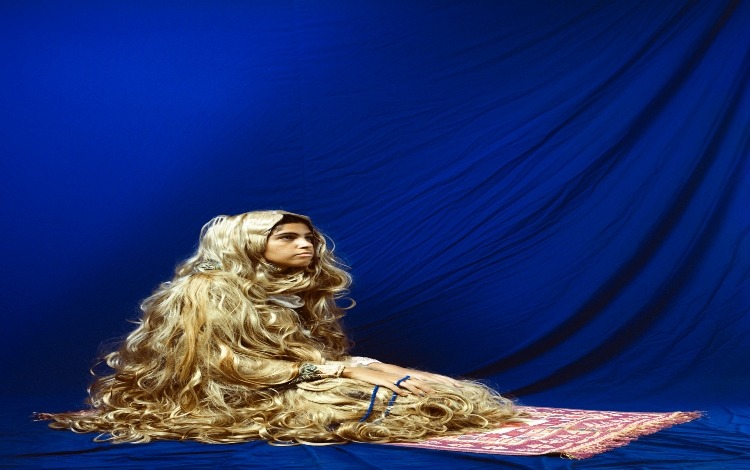

A pure example would be the woman with blonde hair or green eyes. She may have lighter skin, even dress differently, but we idolize her differences nonetheless. Said portrays this perfectly in her piece ‘There Was No

Answer,’ where the costume was made out of blonde hair to subtly tackle the hypocritical and

often deceptive understanding of femininity in the Middle East. As an Arab woman swayed by these selective societal ideologies, it triggers me to ask: Why is it that society feels that they get to determine a woman’s standards of beauty? And, why is it that they get to cherry pick what contributes to a woman’s femininity and what

doesn’t?

If you look closely, whether in the streets, at home, or as portrayed in Najla’s pieces, there is a

space among Eastern women that is never fully embraced. It is not just men that confine this

space, but women too, or any member of society who – consciously or unconsciously – abides by

this patriarchal ideology. Women shrink themselves on a day to day basis, as there are so many

rules dictating what they can and can’t do, or what they should and shouldn’t look like. Whether

it’s their clothes or their hair, or even the language considered ‘appropriate’ for them to use. Even

the satirical use of ‘Okhty, Ya Okhty,’ where the artist expands on the importance of an Egyptian

woman’s capacity to express herself freely, yet titles the woman in reference to someone else, is

the highlight of where the issue lies. Ultimately, we are now in a time where an Egyptian

woman’s representation is established and determined by society. It is also now the time to shift

to a place where such a representation is established upon her own ideologies instead.

It is time to open ourselves to infinite meanings of femininity. It is time to reach a setting in

which a woman – whether in the East or West – can be whoever she wants, and can personify

herself in whatever way she feels fit. It is time that we realize that this lacking power, this limited

freedom, starts by us as women taking a space that should not be outlined by men or other

women, and more meaningfully, by us drawing our own picture that doesn’t belong to someone

else’s sketch. As Najla Said so beautifully points to each and every woman, “This can be you and

the power is yours.”