Thair could feel the frostbite creeping ominously through his limbs and to his fingertips and toes as he swayed unnervingly to and fro on the ship deck of an overcrowded fishing vessel.

As he gazed unsteadily from his left to his right, his eyes fell upon staggering numbers of elderly and pregnant women and small children among the 234 other hopeful refugees aboard the boat.

His eyes traced unrelenting determination on some faces, agonizing suffering on others, and a palpable uncertainty and panic on all, including what he was sure also his own.

Before despair took over his emotions, he reminded himself to focus on something positive, anything positive. At least it was daytime and the refugees surrounding him existed as visible human beings, instead of unrecognizable shadows and silhouettes.

When the sun set, he knew the nighttime would bring more icy chills; there would be nothing to dry the waves that rhythmically splashed over his shivering body. In order to silence such thoughts, he reminded himself that Italy lay somewhere beyond the vast horizon and a smile somehow returned to his face.

In July 2012, on a morning seemingly like any other in the town of Jobar, located less than 10 km outside of the Syrian capital of Damascus, Thair awoke to the deafening sound of tanks firing rounds of ammunition and bombs exploding nearby.

Instinctively, he hopped out of bed and called for his mother and sister with terror resonating in his voice. Thair, his sister, Hania (28), and his mother instantly realized that the war had reached their town and, to ensure their safety, they would have to flee their home without a second thought.

The three of them hurried to a nearby shelter and took refuge in a garage for five exasperatingly long days and nights until it became clear that the turmoil was escalating too rapidly for them to remain stagnant.

Thair remembers the situation with vivid clarity, “I had a strong pain in my chest and felt that I would go crazy. This war is making a lost generation of traumatized children. I am so angry when I think about this.” So, they fled to Lebanon knowing that they risked arrest, and its potentially lethal consequences, if caught.

When I asked Thair about his childhood, he spoke of his home nostalgically, “My house was so, so beautiful. Once the bombs came, I was so sad they we had to leave quickly because we could not take anything with us. We just wanted to survive. I really wish I had run to the living room, opened the closet, and taken our beautiful family photos. My dad also had a collection of Fairuz and Um Kaltoum records in that closet, but they are lost or destroyed with the house by now. Every time I think back to it, I become sad and melancholic. Will I ever see our family house again?”

As a child, Thair loved to learn from everyone and everything, especially his eight siblings — six brothers and two sisters, and he is the youngest. He recalls working alongside his brothers in their car shop and absorbing all kinds of information about cars and business. When he reminisces on these times with his eyes closed, the senses all rush back, “I loved walking in the streets of Damascus early in the morning and smelling the wonderful jasmine flowers. Damascus, my beloved city of jasmine, when will I see you again?”

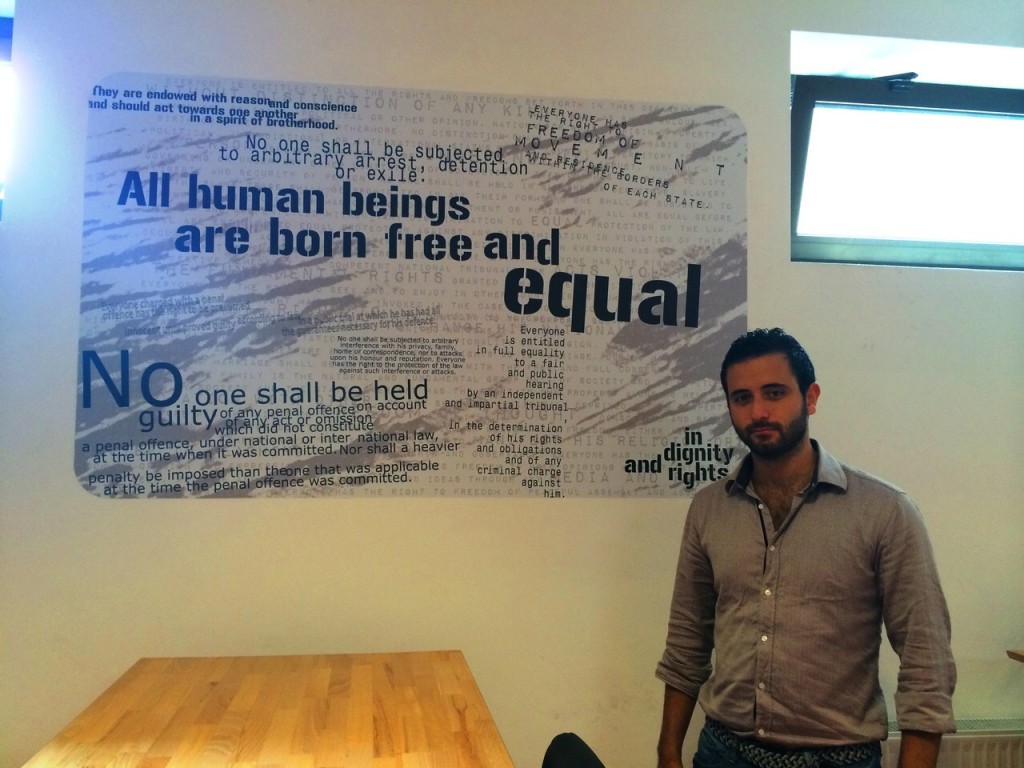

Before the war broke out in Syria, Thair was an ambitious lawyer in the making. While he remained determined to achieve his overall goal of becoming a human rights lawyer, he knew that he must suspend his dreams for the time being, yet he refused to abandon them.

Jobar, Damascus and Syria were his home, but each passing day, increasing numbers of men were disappearing from his community — friends included. These men were either forced to fight in the Syrian Army or imprisoned if deemed adversaries of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, and Thair wanted to avoid being part of their category.

Once Thair reached Lebanon with his mother and sister, he began studying international law in Beirut, but safety still appeared a distant ideal. He caught wind of a number of reports citing violence and kidnappings of Syrians by Hezbollah, which is aligned with the Syrian regime.

Thair feared that he would be caught by this militant group and sent back to Syria to fight on its behalf. This was something he refused to do, so soon he found himself on the move once again, but this time he was alone. Thair’s mother suggested that he go to Egypt because she was afraid for his safety and eventually, his mother and sister, Hania, returned to Damascus in 2012 so Hania could resume her studies.

Before departing Beirut, Thair bid his mother, sister and best friend farewell as he handed over his laptop and begged his friends to ensure his family’s safety. Eventually, he found himself in Egypt.

Upon arriving in Egypt, Thair reconnected with his Italian friend named Sara Bergamaschi after four years of separation. She would quickly become his closest confidante and a second sister to him throughout the journey.

Thair and Sara met in 2009 at the Arab International University in Damascus and he dotingly reflects on their first meeting as “my fondest memory and most beautiful time. We just clicked. We both truly, deeply love life and all the good things about it. We love traveling, smiling, laughing, and being positive. Most importantly, we value friendship. She really changed my life.”

He was 19 and she was 24 and their bond was immediate even though they couldn’t communicate in a common language (at that time, Thair didn’t speak any English and Sara did not speak Arabic, but they are fluent in both languages now).

During his first year in Egypt, Thair resumed his legal studies and began to help fellow refugees through his involvement in a grassroots organization called the Sina Network.

The Sina Network helps refugees — mostly Eritreans, Iraqis Palestinians, Somalis, Syrians and Sudanese — who are in Egypt by providing them with basic needs (shelter, food, clothing, security, health services) and making their voices heard on a global scale. They also work on capacity building among refugees within the network by fostering solidarity between refugees and host communities.

Thair worked with the Sina Network with Sara on weekends, but during the week he studied in Alexandria and eventually graduated from the Faculty of Law in Alexandria in December 2013. To his surprise, considering his isolation from his home, family and previous life in general, he was relatively happy. But sadly, pleasure cannot exist without suffering just as brightness cannot exist without darkness.

As the expiration of Thair’s student visa was fast approaching, he began attempting to acquire a work permit for employment in Egypt to begin his law career. As soon as he began inquiring into the work permit process, he was informed that he needed a permit, a mere sheet of paper, from a legal syndicate of his own country, Syria.

Thus, in order to begin working in Egypt, he would be required to return to Damascus and, considering how far he had come, that was simply out of the question. Shortly after he learned this disheartening and unjustly bureaucratic piece of information, his passport was stolen while he was on a train from Alexandria to Cairo.

When he reflected on the incident, he said, “I didn’t even notice I was pickpocketed. Syrian passports can be sold again in Egypt. My life was broken into pieces. When you are a refugee, your passport is everything you have. When I reported the theft to the Egyptian police, they told me that I was lying and they threatened deportation.”

The Syrian Embassy denied his request for a new passport. Despairingly, he remembers, “they would only issue a travel document that would allow me to fly back to Lebanon and then enter Syria, which would have meant my immediate death.”

When I asked there about his participation in Egypt’s pro-democracy demonstrations and protests, he poignantly said, “I have always been afraid of politics because people used to disappear very quickly in Syria if they showed dissent or complained about the regime. When everything started in Egypt in 2011, it was a fair demand from the people. It was a demand for justice and fair treatment; it was a demand for freedom, which, ultimately, is every person’s highest and dearest thing. Without freedom, we lose our humanity, our capacity to interact with the people and the world around us.”

WE SAID THIS: Stay tuned until next week for the rest of Thair’s inspiring story.