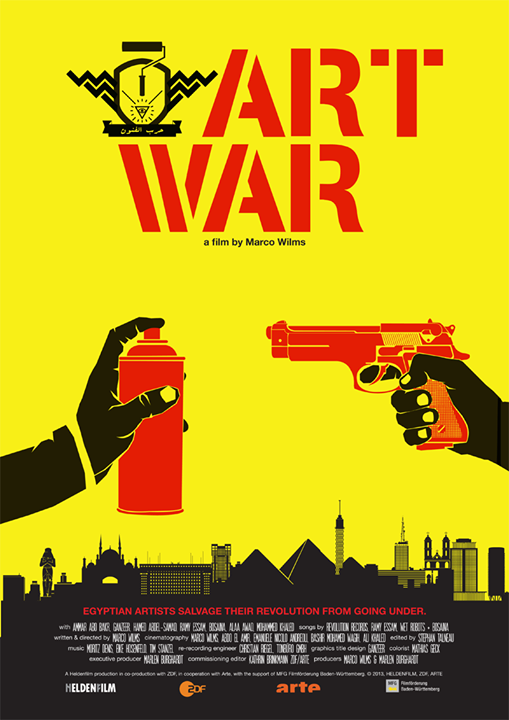

Over the past three years, a great number of films dealing with the Egyptian uprising, whether documentary, docufiction or pure invention have been brought to screens and festivals around the world. The latest such offering I have watched, Marco Wilms’s documentary ART WAR, is an interesting and polarising case.

“ART WAR is the story of young Egyptians who, through art and enlightenment, and inspired by the Arab Spring, use their creativity to salvage the revolution. Using graffiti murals and rebellious music and films, they inspire the youth culture around the world and throughout the streets of conquered Egypt.

The film follows revolutionary artists through 2 years of post-revolutionary anarchy, from the 2011 Arab Spring until the final 2013 Parliament election. It describes the proliferation of creativity after Mubarak’s fall, showing how these artists learn to use art in new ways–as a weapon to fight for their unfinished revolution.”

It is a well-made film, with some truly impressive images, an engaging soundtrack, a tightly-edited narrative structure. A film that follows the actions of four artists over three years, Wilms picks out the most visible events of the Egyptian revolution, highlights their motivations and production at various stages of the uprising.

It is a kick of artistic energy in the pants and a reminder of the long memory that walls have. It is a subjective exploration of the arts as a means of recording and resistance and expressing personal politics. It is a tale of peaceful revolution in the midst of street battles, arrests, deaths. It is a tale of those that have become the memory of the Egyptian uprising, the writers of the first draft of history.

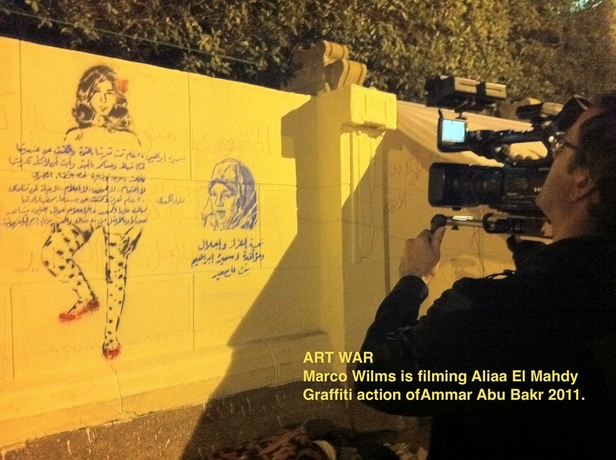

His four main protagonists – Ganzeer, Ammar, Hamed and Bosaina – come from very different backgrounds and may be said to represent the various factions involved in the uprising. Ganzeer, a multifaceted graphic designer from Cairo, adopts methods of direct participation and expands the Egyptian world-view on sexuality and women’s desires.

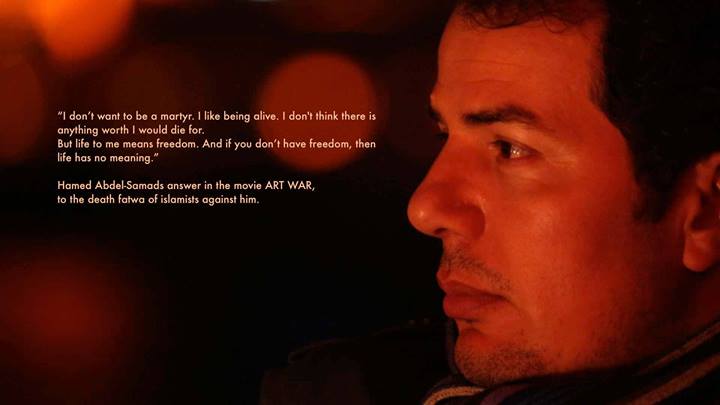

Ammar, from Luxor, is a classically trained artist with an almost pharaonic penchant towards large-scale murals he considers to be the newspaper of the revolution. Hamed, the writer and militant anti-Islamist, provokes and reflects in equal parts. The recipient of death threats from the Muslim Brotherhood, and later abduction by forces “unknown”, he is almost as radical as those he opposes.

Bosaina, a electro-pop singer reminiscent in style and content of a tamer version of the Berlin band Peaches (“Fuck the Pain Away”), admits that she has segregated herself from the mainstream of Egyptian society – “It’s easier”, she tells us.

We also see some others: Rami Essam, a singer who rose to fame during those 18 days between January 25 and February 11, 2011; Alaa Awad, a mural artist who employs contemporised ancient Egyptian motifs to express himself; Ammar’s teacher – the relation between them remains tenuous; a Salafi PR person, who has very white teeth and shows us the anti-secular propaganda.

We visit Sufi ceremonies in Upper Egypt. A Muslim Brotherhood demonstration. Many brief glimpses into lives along the lines of an uprising, its ups and downs. But they remain glimpses out of context.

In spite of a timeline that guides the viewer through the events that surround the “art war”, ongoing in Egypt, it is hard to put the scenes of the film in relation to the events of the last three years. At times, lost between the internal chronology of the film and the timeline of the Egyptian uprising, I found myself asking which narrative to follow and adhere to.

The context of the actions is very sparsely explained, except in the case of the Port Said Massacre. My biggest disappointment was the brief image of millions of Egyptians taking to the streets to topple Morsi, omitting to mention the Tamarrod campaign that led up to it and with only a brief comment on the broken electoral promises.

And then the film ends, leaving us with the impression that events in Egypt end with the rise of the military to power – and that Egyptians always wanted a military dictatorship to be instated.

Although this is more indicative of when the photography of the film ended – around the 5th of July 2013 – it is also representative of a film that chooses to elicit emotions from its audience, rather than inform them about the history of the events that it depicts.

While this is a valid, filmic, approach, it is also one of the dangers of watching that film without prior knowledge of the events that unfold within. It is not a film that asks questions, nor is it one that adds to the information already available. Rather, it chooses to show the audience moments of artistic heroism and defeat, catering to the mainstream with luscious pictures, the energy of a teenager in rebellion and very rare moments of insight.

Even though it offers some interesting reflection on graffiti and public art as a medium of grass-roots expression, it does not follow this reflection with much depth.

Another note has to be made of Bosaina, she of the Wetrobots. This comes in the form of the admission that I have a more than passing familiarity with the Cairo arts scene, and so far, those that have heard of her do not live in Cairo.

She represents an edge to sexual liberation that the city finds hard to accept, with her lyrics laden with sexual references and not-so-innuendo. She is booed out of Cairo Jazz Club by an audience who cannot relate to this woman wearing a full-body leopard print suit. She converses with her friends in English – the only character in the film to do so continuously – and cries.

While her inclusion in the film does allow an exploration to another angle of an art war, the personal battle for acceptance of a different point of view and sexual liberation, she caters more to the eyes and ears of a Western audience than that of the local scene. She is later to leave Cairo, vowing not to perform in Egypt again – for a while at least.

The third note is of the trips Ammar takes to upper Egypt. Even though, once again, the film treats us with beautiful pictures, we are never given enough background to fully understand those pictures in the context of the art war. Sufi shrines – certainly an inspiration for the artist. A feel of sun-boat ceremonies – a breath of air. Yet both out of place in the world Wilms creates for his audience.

The revolution is hardly mentioned in these segments, nor are the events that happen within used to illustrate any discernible point. They are a welcome escape from Cairo, but that is where the film leaves them.

Finally, the film feels very much like it was produced for a Western audience, looking for highlights, heroes and inspiration, rather than political process and backgrounds in the Egyptian uprising. It simplifies the complexity of Egyptian society and discards many processes that have led to some real changes, which is partly due to the limits of the medium, but also owes a lot to the perspective of the authors.

And maybe this is my main issue with the film: While it holds up well as a piece of entertainment to be consumed, enjoyed, then forgotten, it does not leave me with the satisfied feeling of having watched a finished piece of cinema.

There are 120 hours of material available to the filmmaker. His film may benefit from an extra 15 minutes, which, spread around the film, would add the much-needed context that so far eludes him.

I watched it twice, thanks to some very peripheral involvement, and come out of it with this: If you are expecting a film that explores the contexts of the Egyptian Uprising of 2011 in depth and allows for new insights into a society on the brink of transformation and collapse, don’t watch this one.

If you are interested in the Cairo art scene, have an active engagement in graffiti, street art and electronic music, some background on the “Arab Spring” and are looking for an evening’s entertainment, this may be the one for you.

WE SAID THIS: Don’t miss our film review of Excuse My French (Lamo 2akhza) and our Q&A with Director Amr Salama.