When you hear Egyptian music that feels both familiar and refreshingly different, there’s a good chance Fathy Salama had a hand in it. A pianist, composer, arranger, and producer, Salama has long shaped the soundscape of modern Arab music—not by copying trends, but by weaving together his musical roots with new ideas.

Early Life and Musical Foundations

Salama was born in Cairo in 1951, and raised surrounded by the music of his time—icons like Umm Kulthum, Mohamed Abdel Wahab, and Farid Al-Atrash were part of his musical upbringing.

He began formal piano training when he was very young, and by age thirteen was already playing live at Cairo’s clubs. Those early gigs included everything from western rock covers of Rolling Stones and Deep Purple to experimental instrumental pieces and Arabic pop arrangements.

Sharkiat & Innovation

In 1988, Salama formed Sharkiat (“Orientalists” / “Easterners”), a group that became a vessel for his experiments—combining jazzy harmonies, classical training, Arabic scales, and rhythms. For Salama, the aim was never to mimic Western jazz, but to let the traditions he grew up with interact naturally with what he learned elsewhere.

And over decades, Sharkiat played hundreds of concerts around the world—Europe, Africa, jazz festivals, world music stages—and has helped push forward an idea of what Arabic music can be if freed from rigid categories.

The Grammy & Wider Recognition

But the critical turning point came in 2004, when Salama won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary World Music Album, for his work producing Egypt by Senegalese artist Youssou N’Dour. This win was historic: Salama is often described as the only Arab artist to have won a Grammy.

In interviews, Salama has downplayed the Grammy’s impact on his life. “It didn’t affect my life. It was never my aim to get a Grammy. My aim is to keep on learning and doing good music,” he said in one interview. “If I win a Grammy, that’s cool. When it comes to here (Egypt), no one knows about a Grammy anyway, so it didn’t affect me.”

For him, the award was not a finish line but simply one moment in a much longer journey of exploration and self-discipline—one driven by his desire to evolve musically while staying rooted in Egyptian and Arab heritage.

Mentoring, Workshops, and “Sufism vs Modernism”

Beyond performance, Salama was invested deeply in passing the craft forward. He led workshops focused on harmony, arrangement, mixing—areas many young musicians overlook. Through these, he’s nurtured artists who are now integral names in the region’s contemporary music scene.

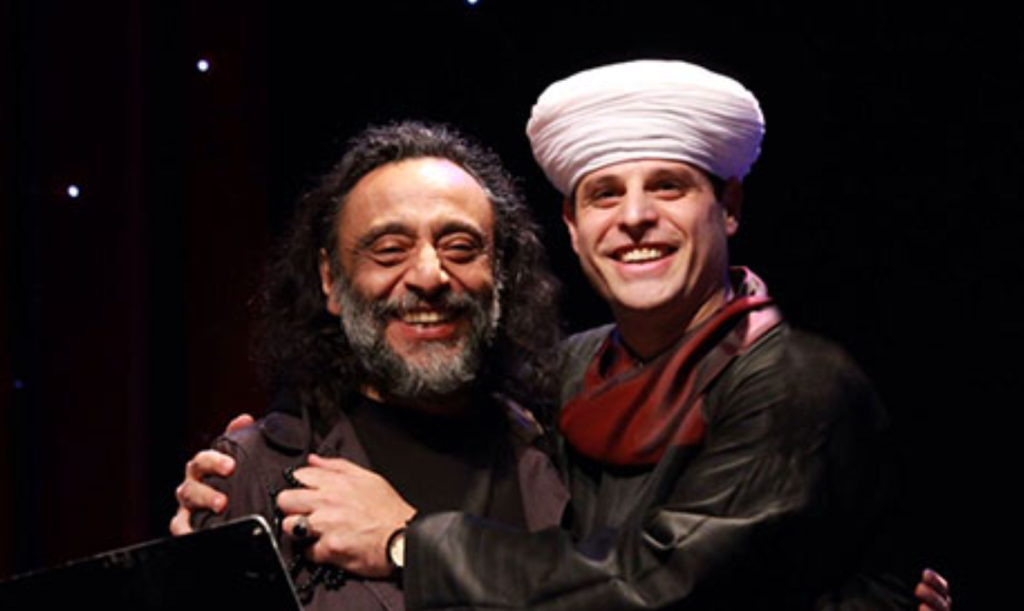

One of his signature projects is Sufism vs Modernism, in collaboration with Sheikh Mahmoud El-Tohamy. The idea: bridging Islamic Sufi chanting and spiritual music with modern arrangements and jazz/harmony, to both preserve tradition and present it in new light.

Style, Values, and Legacy

What makes Salama’s work stand out is that he doesn’t see tradition and modernity as opposites, but as layers. He draws from Arabic scales, Sufi chants, folk melodies—but then he’s unafraid to integrate them with improvisation, rhythm, harmony, even electronic textures. His philosophy is that you respect what you come from, while not being trapped by it.

In recent years, Salama has reflected on how the region’s music scene has shifted toward mass appeal and digital popularity. Yet, he continues to advocate for artistry rooted in substance and heritage, dedicating much of his time to mentoring young musicians and supporting initiatives that prioritize musical education and craftsmanship.

Why His Grammy Matters—But Not Too Much

The Grammy is often what many outside the Arab music world hear first about him. And yes, it’s significant—global recognition, peer-approval. But in Salama’s own view, it’s not what defines him. What defines him is consistency: staying engaged, pushing boundaries, and preserving the musical vocabulary of his heritage even while transforming it.

Fathy Salama may be celebrated for being the first Arab Grammy winner, but his real achievement is quieter: creating a space where tradition knows how to stretch, where a melody from a village or a Sufi chant can sit next to improvisation or jazz harmony—and together make something neither old nor new, but deeply alive.

WE ALSO SAID THIS: Don’t Miss… The Story of Egyptian Rap: From the Streets to the Spotlight