From the banks of the Nile to the grand halls of museums across Europe, Egypt’s ancient wonders continue to capture imaginations everywhere. Over time, many of these masterpieces have traveled far from their original homes — their journeys shaped by exploration, empire, and history itself. Today, they remain ambassadors of Egyptian civilization, admired globally yet rooted deeply in the story of one nation.

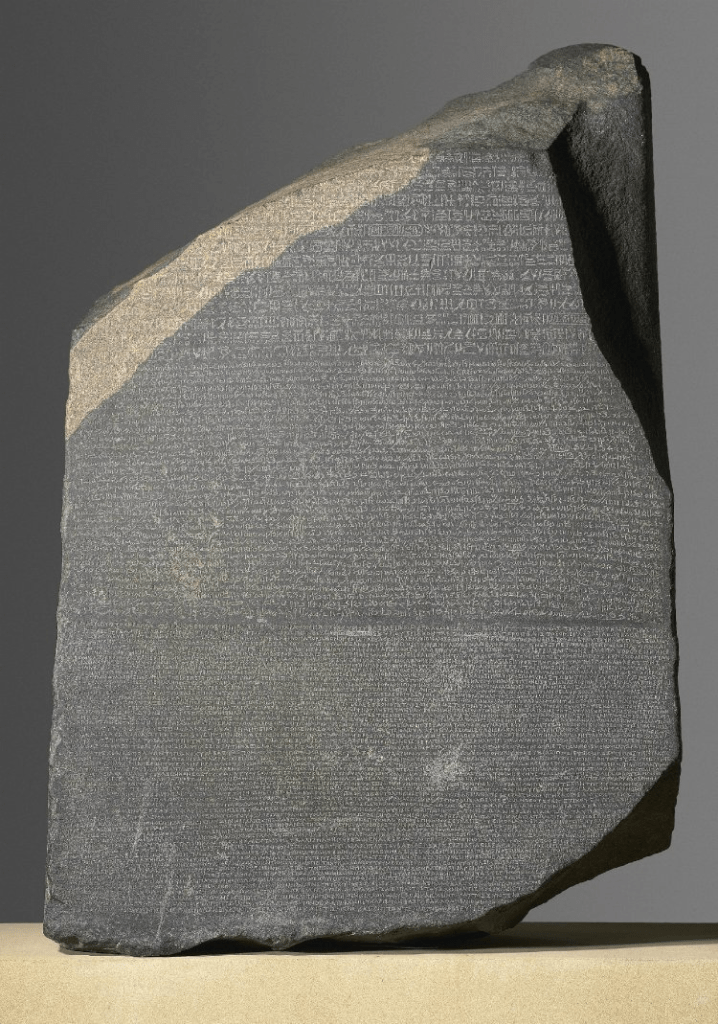

The Rosetta Stone – British Museum, London

Few discoveries have changed our understanding of ancient Egypt as much as the Rosetta Stone. Unearthed in 1799 near the city of Rosetta (modern-day Rashid) by a French officer during Napoleon’s campaign, this granodiorite slab bears the same decree inscribed in three scripts: hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek.

That simple fact — one text, three languages — became the key to unlocking the mystery of hieroglyphs after centuries of silence. The Greek portion revealed that the inscription honored King Ptolemy V, while its repetition in hieroglyphs allowed scholars to finally decode Egypt’s sacred writing system.

Since 1802, the stone has been on display at the British Museum, where it draws millions of visitors a year. Beyond its fame, it’s a tangible bridge between civilizations — proof that Egypt’s language was the foundation upon which so much of human history was written.

The Bust of Nefertiti – Neues Museum, Berlin

Arguably one of the most famous faces in the world, Queen Nefertiti’s limestone bust has become an icon of timeless beauty and artistry. Discovered in 1912 at Tell el-Amarna by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, it dates back to around 1340 BCE, during Egypt’s revolutionary Amarna period.

Painted in vivid tones that have survived more than 3,000 years, the sculpture’s delicate features — high cheekbones, long neck, and serene gaze — embody an ideal of grace that still feels modern. The unfinished back of the bust and the fine guidelines traced across her face hint at its creation inside a sculptor’s workshop — a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the craft of royal portraiture.

Now displayed in Berlin’s Neues Museum, the bust attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

The Tarkhan Dress – UCL Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Older than the pyramids themselves, the Tarkhan Dress is the world’s oldest known woven garment — dating back more than 5,000 years to Egypt’s First Dynasty. Unearthed near Cairo by famed archaeologist Flinders Petrie, it was nearly overlooked when first excavated, mistaken for a bundle of rags until conservationists rediscovered it decades later.

Tailored from fine linen with narrow pleats, a V-neck, and fitted sleeves, the dress reveals astonishing sophistication for its age. Unlike most ancient textiles that crumbled long ago, this one survived almost intact — creases at the elbows and armpits even suggest it was once worn by someone of high status.

Now preserved at London’s Petrie Museum, the dress isn’t just a relic of fashion — it’s evidence of a prosperous, complex society that valued craftsmanship and beauty at the very dawn of Egyptian civilization.

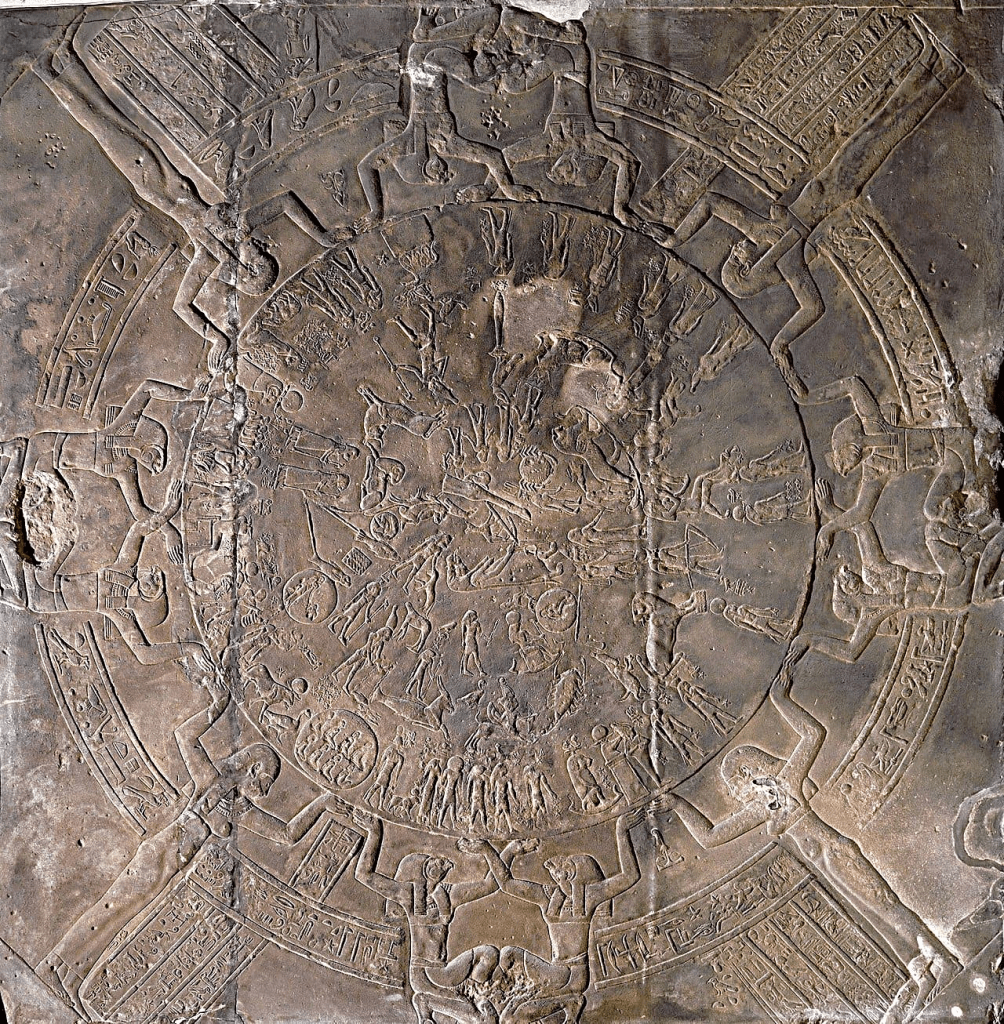

The Dendera Zodiac – Louvre Museum, Paris

Carved around 50 BCE into the ceiling of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, the Dendera Zodiac is one of the most extraordinary star maps in antiquity. This circular sandstone relief depicts zodiac symbols, planets, and eclipses as seen through an Egyptian lens — a cosmic tapestry that merges science and spirituality.

The zodiac shows an alignment of the five known planets in a configuration that happens only once every thousand years, allowing modern astronomers to date the scene to the summer of 50 BCE. Many believe it was created to mark the reign of Cleopatra VII and the death of her father, Ptolemy Auletes — a celestial reflection of power and continuity.

Now housed at the Louvre, the relief stands as a symbol of how the ancient Egyptians saw their world: one where the divine order of the stars guided both kings and commoners alike.

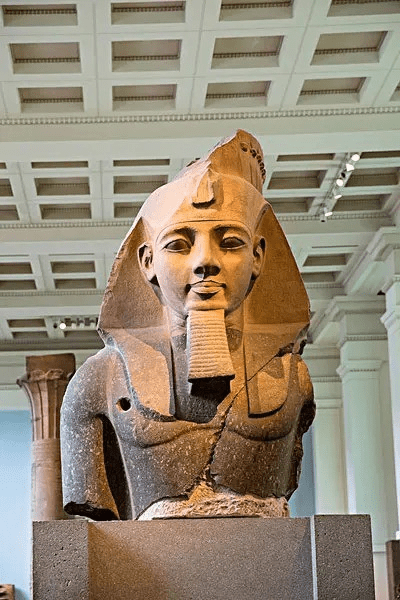

The Younger Memnon (Head of Ramesses II) – British Museum, London

Commanding and eternal, this colossal pink and grey granite head of Pharaoh Ramesses II once stood at the entrance to his mortuary temple in Thebes. The sculptor even used the two-toned stone to emphasize the contrast between the pharaoh’s features and his body — a subtle artistic flourish that highlights the sophistication of Egyptian craftsmanship.

Standing at 2.7 meters tall and weighing around 20 tonnes, it is the largest Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum. Traces of red pigment suggest it was originally painted, its color now long faded but its power undiminished.

For many visitors, the calm expression and strong jaw of Ramesses II embody Egypt’s enduring grandeur — the image of a ruler who once declared himself “King of Kings,” his likeness surviving millennia and continents.

Cleopatra’s Needles – London & New York

Despite their modern nickname, Cleopatra’s Needles predate her by over a thousand years. Originally carved during the reign of Thutmose III around 1500 BCE and dedicated to the sun god Ra, these towering red granite obelisks once stood proudly in Heliopolis before being moved to Alexandria during the Roman era.

Each stands about 21 meters tall and weighs over 200 tons — astonishing feats of engineering that required both immense skill and manpower. Their surfaces are covered in hieroglyphs honoring Thutmose III and Ramesses II, preserving the voice of Egypt’s golden age.

In the 19th century, the obelisks were re-erected in London and New York where they became emblems of empire and fascination. Yet even abroad, their hieroglyphs still whisper the same story — of pharaohs, gods, and the land of the sun that gave birth to them.

A Legacy That Spans Continents

From the Rosetta Stone that unlocked a lost language to the Tarkhan Dress that rewrote the history of fashion, these treasures are far more than museum pieces. They are fragments of Egypt’s soul — living testaments to a civilization that shaped art, architecture, science, and belief.

While their presence across the world allows millions to encounter Egypt’s past up close, their stories will always trace back to one source: the land that gave humanity its first kingdoms, its first written words, and its timeless sense of wonder.

WE ALSO SAID THIS: Don’t Miss…The Heroes Behind the Grand Egyptian Museum’s Historic Opening