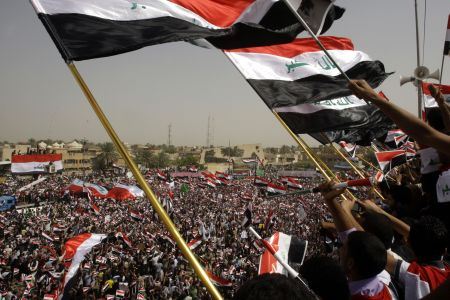

Over the last weeks, thousands of protests, including strikes and sit-in, have taken place in Sunni-dominated areas, notably north and west of Baghdad, calling for the satisfaction of mainly two demands: the release of hundreds, if not thousands, of prisoners charged with terrorism by virtue of Laws adopted under the umbrella of the “war on terror” but according to many, arrested out of sectarian animosities (most of them have been freed this week-end, the authorities having admitted that some of them were arrested “unlawfully” though blaming bureaucrats for this) and the resignation of the Shiite President Nuri Al-Maliki. Like their brethren in neighbouring countries, demonstrators (the conditions of most of them have not changed since 2003) also call for the improvement of economic conditions, for an halt to marginalization and ghettoization of minorities, for a better education, for more transparency, for jobs and, above all, for justice and equality. The protests have been met with a carrot-and stick approach: Maliki announced the eventual release of prisoners, but has also warned his opponents, accusing them of being hijacked by groups to harm the national interest, against keeping them up, for they “violate the Constitution” and that would allow him to legitimately resort to force.

The demonstrations have increased in size and intensity within the Sunni minority, dominant with ousted dictator Sadam Hussein but target of most acts of violence after the US intervention and the consequent overthrow of the tyrant, and have coincided with a string of attacks targeting Shia gatherings and politicians, raising concerns about a resumption of the 2006 bloody episodes. Some would think these rallies have to do only with an enmity deeply embedded in Iraqi society, particularly as an immediate consequence has been the persecution of high-profile Sunni authorities and their entourage (notably within the security forces) often used as scapegoats (this time it was the Sunni Finance Minister; last year, it was the Vice president Tariq al-Hashimi who was involved in this type of hounding, being finally forced to flee the country, before being convicted in absentia and sentenced to death) but, surprisingly, they have even received the backing of a controversial populist Shia cleric, Muqtada Al Shadr, who has even warned of an “Iraqi Spring”. Moreover, tensions have not been abated as in previous occasions, for the Kurdish President, known to be a highly appreciated successful mediator, is still ill after suffering a stroke last December. Therefore, is this a case of a merely sectarian uprising, or is the state confronted with a more serious national awakening? Does the latter only target President Maliki, or is the whole Government under threat?

The Iraqi President, whose party, Dawa, is part of the broader Shiite-dominated National Alliance, stands nowadays as an incredibly controversial figure. As of lately, he has been showing increasingly authoritarian, corrupt and anti-democratic, to the point that The Economist has dubbed him a “would-be dictator”. Provincial elections (first vote to take place after the Americans definitely got out of the country) are due to take place next April, and Mr Maliki is supposedly already maneuvering with the aim of sidelining his rival Sunni, but also Shia, political opponents. These accusations are not that surprising if we take into account Maliki, who took power in 2006, gained a second term as Prime minister in 2010 in the midst of a moot process that kicked off after a round of parliamentary elections whose results are still not crystal clear. In this sense, the President has also been accused of fueling already existing crises or opening new fronts in order to stay in power, notably discretely fanning sectarian tensions between Shias and Sunnis Maliki has also upped the ante between Baghdad and Erbil, capital of the autonomous oil-rich Northern Kurdish region that still claims more territory and power, where tensions escalated after his sending soldiers to Kurdish territories last December.

As if that wasn’t enough, the President has become more and more both supportive of Assad´s repression and dependent on Iran’s support (some of the rallies interestingly call for “the fall of the Safavid-Persian alliance”), clearly showing that any conflict in Iraq could be considered as one of many spill-overs of Syria´s civil war. Militant Sunnis have been going to Syria to fight against Assad’s regime for months. Now, Iraqi Shiites are joining the battle but on the government’s side, raising the likelihood of a renewed latent civil conflict. Already in response to the growing civil war in Syria, violence has spiked in the country and Al-Qaeda is said to be resurgent there. Indeed, and even though many people bet on a domino-effect taking a huge toll in Lebanon, chances are that the lion´s share of a regional conflict will have to be borne by the Iraqi population. Contrary to years-long war-torn Lebanon, Iraq is a country where the different factions have not learned yet to strike a real balance of power, and thus avert an all-out conflict.

Once again, the stark contrast between Lebanon and Iraq has to be stressed. Even though it was vastly hailed by many pundits throughout the world, the 2005 Constitution (Karl Loewenstein would surely have called it a “nominal text”) has shown no sign of being able of bringing back together rival factions or, for that matter, of guaranteeing any kind of stability and respite to the population. The chief aim of the Chart was to put in place a system of sectarian quotes, guaranteeing a representative role both to Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. This has however given way to a clientelist system where what matters more is mastery of rhetoric, sectarian affiliation, building networks, becoming increasingly media-savvy and skimming plots to cling to power.