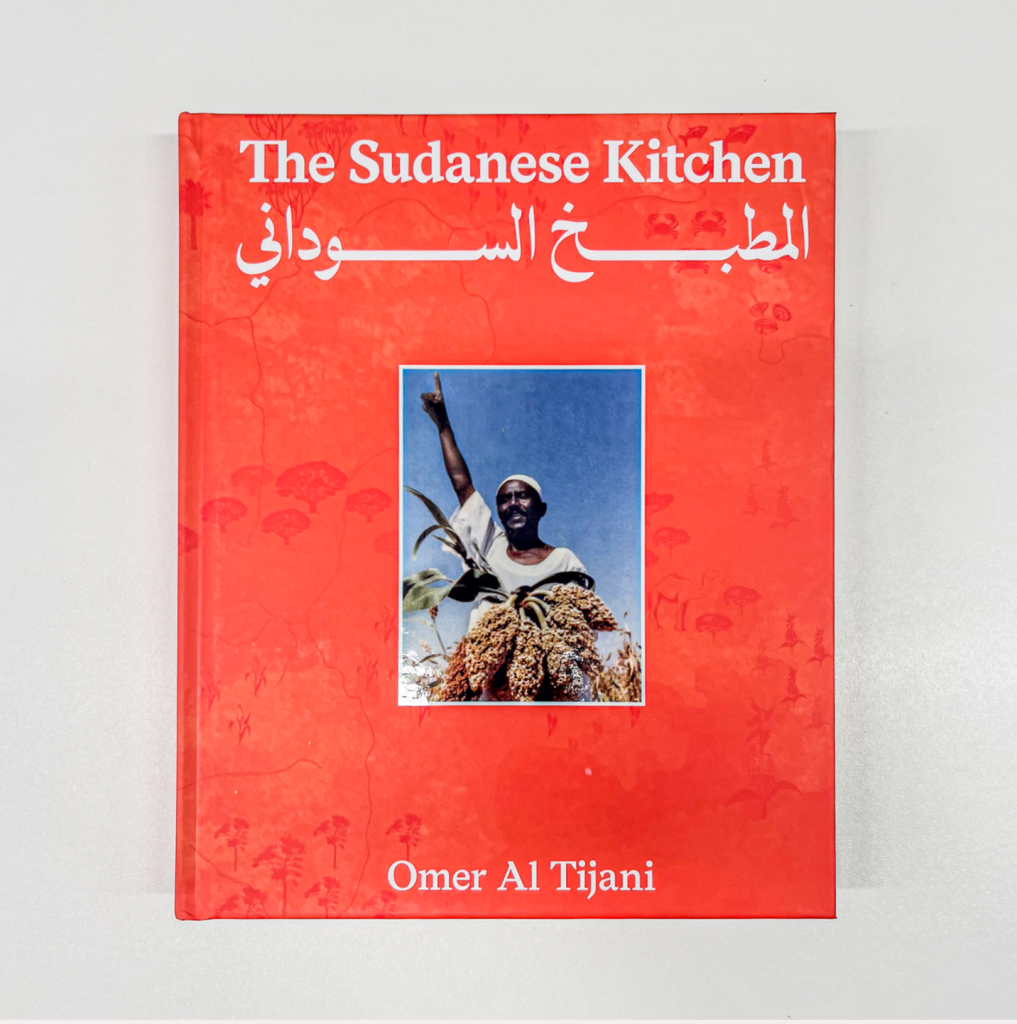

For Omar Al Tijani, The Sudanese Kitchen has always been something deeply personal. Living away from home, he began collecting family recipes—small culinary memories that helped him carry a piece of Sudan wherever he went. One that tells a story—however small—about his people, to the world.

In our conversation with Omar Al Tijani, he reflects on how The Sudanese Kitchen grew from a collection of family recipes into the first English-language Sudanese cookbook, preserving the flavors and stories of his homeland for the world to discover.

“I had already gathered some family recipes for myself while living away from home; they were a way to have a piece of home with me at all times,” he recalls. “I went online and discovered that there isn’t a Sudanese cookbook in English—it felt like there should be one. I thought if I don’t do it, then maybe someone else might eventually, or maybe not. It seemed like a fun journey, so I decided to give it a shot.”

What started as a personal archive has since evolved into The Sudanese Kitchen—a landmark English-language cookbook dedicated to the country’s diverse and often under-documented food heritage.

The Elements That Define Sudanese Food

When asked what makes up the backbone of Sudanese cuisine, Al Tijani points to a long history of movement, adaptation, and exchange.

“Local Sudanese foodways came about from nomadic and semi-nomadic groups that cooked stews and served them with fermented local grains—sorghum, millet, and later wheat—such as kisra, asida, and gurasa,” he explains. These staples shaped a cuisine built for endurance and hospitality, relying on ingredients that could travel easily: dried meats and fish, flour, dried onions, and okra.

Over the centuries, Sudanese food has absorbed influences from across its borders. “Eastern Mediterranean influences have flowed steadily into Sudan for over a millennium,” he notes, introducing mezze-style dishes like falafel, mulukhiya, and bamya. Similarly, “West African influences have reinforced cooking techniques in food preparation such as asida, mullah, agashey, and many local dishes of western Sudan.”

The result is a cuisine that feels both ancient and fluid—rooted in place, yet constantly evolving.

Cooking as a Story

For Al Tijani, every dish tells a story. “Cooking is a form of storytelling, especially when preparing something that holds significance for the cook or the diners,” he says. Traditional recipes, in particular, serve as cultural maps. “This way of cooking reveals a great deal about the group—where they’re from and what might be unique to their locality. Cooking is an exploration of one’s identity.”

That idea runs through the entire project: food as a record of who we are and how we got here.

Archiving Through People

When asked about his approach to documenting food, Al Tijani is quick to credit his homeland. “Sudan is the archive,” he says simply. “Its people are the sources of information that allow me to archive its food. I would have loved to travel further and for longer to document as much as possible.”

Each recipe, in this sense, becomes a document—an entry in a living history that connects communities across geography and generations.

The Dishes That Tell His Story

Among the many recipes featured in The Sudanese Kitchen, two stand out for Al Tijani—both personally and culturally.

“Mullah um rigeiga,” he says, “is a simple stew of ground okra in a meaty broth served with kisra. It may not look great since the ground okra makes it appear slimy, but the taste is excellent and so comforting.”

He also mentions kunafa malfufa—“homemade kunafa pastry filled with crushed nuts, broken dates and cinnamon, glazed in sugar syrup and garnished with desiccated coconuts.” For him, it’s a testament to the creativity of Western Sudanese cuisine: “It’s a wonderfully unique take on the kunafa concept and highlights the innovation of Western Sudanese cooking.”

Building a Community

When Al Tijani began sharing his work online, he didn’t expect the response it would spark. “After publicising The Sudanese Kitchen, I continued to receive messages of encouragement from the online community, both Sudanese and non-Sudanese, which kept the project moving forward,” he says.

“Many Sudanese people felt represented, and they would make requests to highlight certain foods or parts of the food culture. The online community made me realise that I should showcase all Sudanese foods, not just what I’m familiar with.” Through that dialogue, The Sudanese Kitchen became, very naturally, a shared space of rediscovery.

Authenticity and Adaptability

For Al Tijani, the question of authenticity is almost irrelevant. “Sudanese recipes have always been adaptable,” he says. “The same recipe can be made in many different ways. The question of authenticity doesn’t apply to Sudanese foods because they have always been versatile and remain just as authentic.”

This flexibility allows him to adapt recipes for different diets—vegan, gluten-free, vegetarian—without compromising their essence.

The Spirit of Sharing

Sudanese hospitality, he explains, is deeply communal. “Meals are often shared,” he says. “I encourage diners to eat in the traditional Sudanese way so they can experience a different dining experience. It’s often not just what we eat that’s insightful, but also the way we eat that others can learn from.”

That spirit of togetherness, he believes, is something the world could use more of. “This form of sharing meals creates a unique intimacy that’s not often found in other cuisines.”

A Historic First

As the first Sudanese cookbook published in English, The Sudanese Kitchen has been met with pride and excitement. “It’s a historic achievement,” Al Tijani says. “Sudanese are happy to see their cuisine and culture represented in an attractive manner for the world to appreciate. They say it’s the perfect gift between Sudanese and non-Sudanese.”

Looking Ahead

Asked which dish he could eat endlessly, Al Tijani laughs. “I need to have a variety—I get bored easily by eating the same thing,” he admits. But when introducing newcomers to Sudanese cuisine, he always starts with something approachable: “Peanut salad.”

As for what’s next, he hints at something beyond the kitchen. “A film, hopefully.”

And perhaps that’s fitting—because for Omar Al Tijani, storytelling has never been confined to one medium. Whether on a plate or a screen, he’s still telling Sudan’s story—one that, like its food, continues to travel, transform, and endure.

WE ALSO SAID: Don’t Miss…The Story Of JUMA Kitchen: The Iraqi Food Stall In The Heart Of London